Robust regression

For training purposes, I was looking for a way to illustrate some of the different properties of two different robust estimation methods for linear regression models. The two methods I’m looking at are:

- least trimmed squares, implemented as the default option in

lqs() - a Huber M-estimator, implemented as the default option in

rlm()

Both functions are in Venables and Ripley’s MASS R package which comes with the standard distribution of R.

These methods are alternatives to ordinary least squares that can provide estimates with superior qualities when the classical assumptions of linear regression aren’t met. M-estimators are effective in dealing with various breakdowns in the classical linear model assumptions, while still giving excellent results if the assumptions happen to be valid after all. Least trimmed squares is very resistant to outliers, at a cost to efficiency. Unfortunately, neither of these (or any other) robust estimation methods is the best in all situations, although they generally out-perform ordinary least squares in most real-life situations (my own, non-systematic observation).

New Zealand Income Survey 2011

To explore this I use the simulated unit record file from the New Zealand Income Survey 2011 that I’ve used in a lot of blog posts in the past year. My first post on this dataset sets out how to import this data and tidy it up into a database. The data shows weekly individual income from all sources for New Zealanders aged over 15, as well as hours worked and a range of demographic information I won’t be using today. For looking at robust regression estimation methods, I’m going to pretend that I only ever have a sample of thirty observations from this dataset.

To illustrate the data, here’s an animation showing the full dataset (in grey) and repeated different samples of thirty data points, as well as lines representing linear models fit to those small samples with ordinary least squares (lm) and the two robust regression methods I’m investigating today.

Some characteristics of this data that make it a useful illustration for robust regression include:

- It’s reasonable to postulate the underlying relationship between hours worked and income as linear for much of the population. So a linear model on the original scale is likely to be appropriate.

- However, the population seems likely to be made up of a number of diverse groups, making assumptions of homogeneity implausible. For example, a large number of people have incomes, some of them quite substantial, despite working zero hours. General economic and social knowledge suggests that divisions into wage-earners, profit-receivers, and social security receivers probably constitute three quite different populations, while still being a significant simplification of the actual heterogeneity.

- On the original scale the data are expected to show heteroscedasticity (in this case, higher variance for higher expected income), making classical inference invalid

- There are a number of outliers on both the x and y axes; and a cluster of individuals with negative income that appear to form yet another group in the mixture.

Comparing robust methods

To reflect one of the key features of the data which is the unusual distribution of income when working hours are zero, the models fit in this post are all of the structure:

income ~ hours + (hours == 0)

The graphics show just the relationship between income and hours for when a non-zero amount of hours is worked. In effect, (just for the graphics), this is like fitting the model after removing all the individuals that performed zero hours of work in the surveyed week.

The animation shown above was the germ idea for this post and already illustrates the key points. In particular, it shows how the randomness associated with a small sample of thirty points leads to a different result for any particular sample; and once you have that sample, different estimation methods can give you materially differing results. In some frames of the animation, we see a sample of thirty where slopes from the different estimation methods point in different directions, suggesting that if that particular small sample was the only one available, one might conclude that working more hours leads to decreased income.

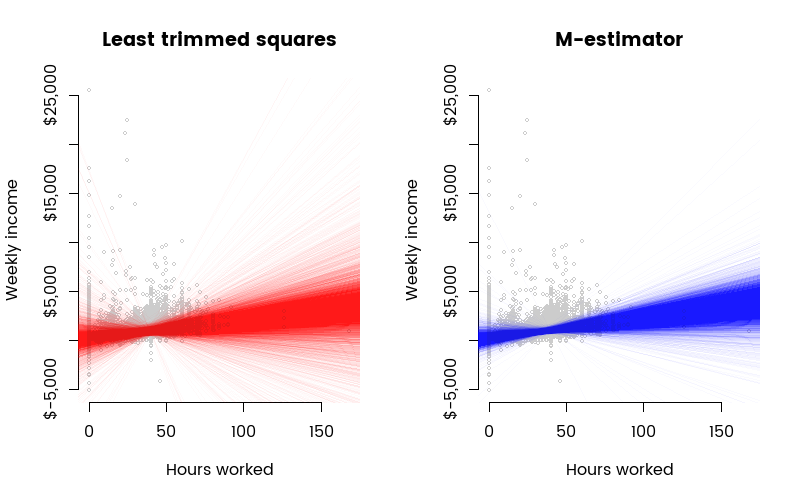

The animation is nice for reminding us of the randomness associated with small samples, but actually isn’t a particularly effective method of looking at how the different robust estimation methods are doing. Here’s a better way of doing that; a plot of the actual regression lines fit to 10,000 different samples of thirty. Each line is semi-transparent, to give a better visual impression of where the bulk of fit lines end up:

This makes it graphically clear that the lqs method (least trimmed squares) gives a noticeably wider range of results than does the Huber M-estimator. This is an expected result; least trimmed squares is highly resistant to outliers, but this comes at the cost of sufficiency (effectively, a significant part of the data has very little impact on the slope, so the information contained in the data is not utilised to the full).

Here’s another way of looking at that; the density plots of the slopes of the three estimation methods (two robust methods plus ordinary least squares fitted with lm). I am using slope because it’s the most likely parameter of interest - it represents the marginal increase in income from an extra hour of work.

The density plot shows that the estimates from lqs tend to be lower than for either rlm or lm. This is to be expected, in a way related to the reason that trimmed mean or median income is usually less than mean income. An estimation method that knocks out of the data the most extreme points (as done by least trimmed squares) will give differing results for samples drawn from skewed distributions.

Here are the mean, median and standard deviation of the slopes estimated by the three methods for the 10,000 samples of thirty:

method mean median sd

lm 21.3 21.9 18.9

rlm 20.5 20.7 10.9

lqs 17.7 18.2 23.7We see that lm and rlm on average give similar results, but rlm is much more stable, with a noticeably lower variance in results (shown by the standard deviation). lqs on the other hand is actually quite unstable, for this small sample size.

Preliminary thoughts on robust regression estimators

This post uses Venables and Ripley’s MASS package and the accompanying book Modern Applied Statistics with S. Their own discussion of the issue implies (to my reading) the preferred use of the MM-estimator proposed by Yohai, Stahel & Zamar in 1991, which retains the outlier-resistance of the S-estimator methods related to trimmed least squares, and the greater efficiency of M-estimators. MM-estimators are available via rlm() with the method = 'MM' argument.

Another book that has been influential for me and I thoroughly recommend is Wilcox’ Modern Statistics for the Social and Behavioral Sciences. His comments on the matter are so pertinent that I am going to quote two paragraphs at length:

Comments on Choosing a Regression Estimator (Wilcox)

“Many regression estimators have been proposed that can have substantial advantages over the ordinary least squares estimator. But no single estimator dominates and there is the practical issue that the choice of estimator can make a practical difference in the conclusions reached. One point worth stressing is that even when an estimator has a high breakdown point, only two outliers, properly placed, can have a large impact on some of the robust estimates of the slopes…. Estimators that seem to be particularly good at avoiding this problem are the Least Trimmed Squares, Least Trimmed Absolute Value and OP regression estimators. Among these three estimators, the OP estimator seems to have an advantage in terms of achieving a relatively low standard error and so has the potential of relatively high power. A negative feature of the OP estimator is that with large sample sizes, execution time might be an issue…

“In terms of achieving a relatively small standard error when dealing with heteroscedasticity, certain robust regression estimators can offer a distinct advantage compared to the least squares estimator…. Ones that perform well include Theil-Sen, the OP regression estimator and the TSTS estimator. The MM-estimator does not perform well for the situations considered (ie heteroscedasticity)… but perhaps there are situations where it offers a practical advantage.”

It should be noted that earlier in the chapter Wilcox pointed out that the MM-estimator “enjoys excellent theoretical properties … but its standard error can be relatively large when there is heteroscedasticity.”

The “OP” estimator is a method of outlier detection and removal followed by Theil-Sen estimation, a method that takes the median slope between all the pairs of sample points. Topic for a future post.

Code

Here’s the R code behind all this. It won’t be immediately reproducible. Prior work is needed to establish the database as described in my earlier post; and the animation sequence is dependent on a particular folder structure.

#===================setup=======================

library(showtext)

library(RMySQL)

library(MASS)

library(dplyr)

library(tidyr)

library(stringr)

library(ggplot2)

library(scales)

library(directlabels)

#================download and transform data==============

# See https:/freerangestats.info/blog/2015/08/15/importing-nzis-surf/ for

# instructions on setting up the database

sql <- "SELECT hours, income FROM vw_mainheader"

PlayPen <- dbConnect(RMySQL::MySQL(), username = "analyst", dbname = "nzis11")

nzis <- dbGetQuery(PlayPen, sql)

dbDisconnect(PlayPen)

# An early version of the analysis used a cube root transform; this was dropped

# as it reduces interpretability and is not really germane to the illustration

# of robust regression methods

# cuberoot <- function(x){

# sign(x) * abs(x)^(1/3)

# }

# nzis <- nzis %>%

# mutate(income2 = cuberoot(income),

# hours2 = cuberoot(hours))

# create the variables to be used for x and y (as finally used, this

# is just income and hours on their original scale):

nzis <- nzis %>%

mutate(income2 = income,

hours2 = hours)

#==================simulations of many samples and estimated models==============

# create empty lists to hold the samples and the model results

points_samp <- list()

mod_lm <- list()

mod_rlm <- list()

mod_lqs <- list()

# create the samples, estimate the models and store the results

reps <- 10000

for (i in 1:reps){

nzis_samp <- nzis[sample(1:nrow(nzis), 30), ]

points_samp[[i]] <- nzis_samp

mod_lm[[i]] <- lm(income2 ~ hours2 + (hours2 == 0), data = nzis_samp)

mod_rlm[[i]] <- rlm(income2 ~ hours2 + (hours2 == 0), data = nzis_samp)

mod_lqs[[i]] <- lqs(income2 ~ hours2 + (hours2 == 0), data = nzis_samp)

}

#======================reporting results==============

#------------setup-----------------

# Fonts:

font.add.google("Poppins", "myfont")

showtext.auto()

theme_set(theme_light(base_family = "myfont"))

# define a generic plot function that does the background pale grey

# plot of the full dataset and draws the axes:

draw_plot <- function(){

with(nzis, plot(hours2, income2, cex = 0.5, col = "grey80", bty = "l",

xlab = "Hours worked",

ylab = "Weekly income",

axes = FALSE))

axis(2, at = axTicks(2), labels = paste0("$", str_trim(format(

axTicks(2), big.mark = ","))))

axis(1, at = axTicks(1), labels = axTicks(1))

}

#-----------animation-------------

# This code is dependent on the particular folder structure. File locations

# will need to be changed if people want to reproduce the analysis.

for(i in 1:100){

png(paste0("_output/0041-rlm-lqs/", i + 20000, ".png"),

650, 650, res = 100)

par(family = "myfont")

draw_plot()

title(main = "Comparison of different estimation methods\nfor linear models on a subset of income data")

with(points_samp[[i]], points(hours2, income2, cex = 2))

abline(mod_lm[[i]], col = "black")

abline(mod_rlm[[i]], col = "blue")

abline(mod_lqs[[i]], col = "red")

legend("topright", legend = c("lm", "rlm", "lts"), lty = 1,

col = c("black", "blue", "red"), text.col = c("black", "blue", "red"),

bty = "n")

legend("bottomright", legend = c("Full data", "Sampled data"),

pch = 1, col = c("grey50", "black"), pt.cex = 1:2,

bty = "n", text.col = c("grey50", "black"))

dev.off()

}

# next sequence turns the various static frames into an animated GIF

# and depends on the actual location of ImageMagick:

projdir <- setwd("_output/0041-rlm-lqs/")

system('"C:\\Program Files\\ImageMagick-6.9.1-Q16\\convert" -loop 0 -delay 65 *.png "../../../img/0041-rtm-lqs.gif"')

setwd(projdir)

#--------------visual static comparison-----------------

par(mfrow = c(1, 2), family = "myfont")

# draw graph for lqs

draw_plot()

title(main = "Least trimmed squares")

for(i in 1:reps){

abline(mod_lqs[[i]], col = adjustcolor("red", alpha.f = 0.02))

}

# draw graph for rlm

draw_plot()

title(main = "M-estimator")

for(i in 1:reps){

abline(mod_rlm[[i]], col = adjustcolor("blue", alpha.f = 0.02))

}

#-----------------compare estimated slopes-------------------

slopes <- data.frame(

lm = unlist(lapply(mod_lm, function(x){coef(x)[2]})),

rlm = unlist(lapply(mod_rlm, function(x){coef(x)[2]})),

lqs = unlist(lapply(mod_lqs, function(x){coef(x)[2]}))

) %>%

gather(method, value)

# summary table:

slopes %>%

mutate(method = factor(method, levels = c("lm", "rlm", "lqs"))) %>%

group_by(method) %>%

summarise(

mean = round(mean(value), 1),

median = round(median(value), 1),

sd = round(sd(value), 1)

)

# density plot, taking care to use same colours for each method

# as in previous graphics:

colours <- c("lm" = "black", "rlm" = "blue", "lqs" = "red")

print(direct.label(

ggplot(slopes, aes(x = value, fill = method, colour = method)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.3) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-25, 75)) +

scale_x_continuous("Estimated marginal return of extra hour of work",

label = dollar) +

labs(y = "Density of estimates from\nsamples of 30 each") +

scale_fill_manual(values = colours) +

scale_colour_manual(values = colours)

))