Motivation and key points

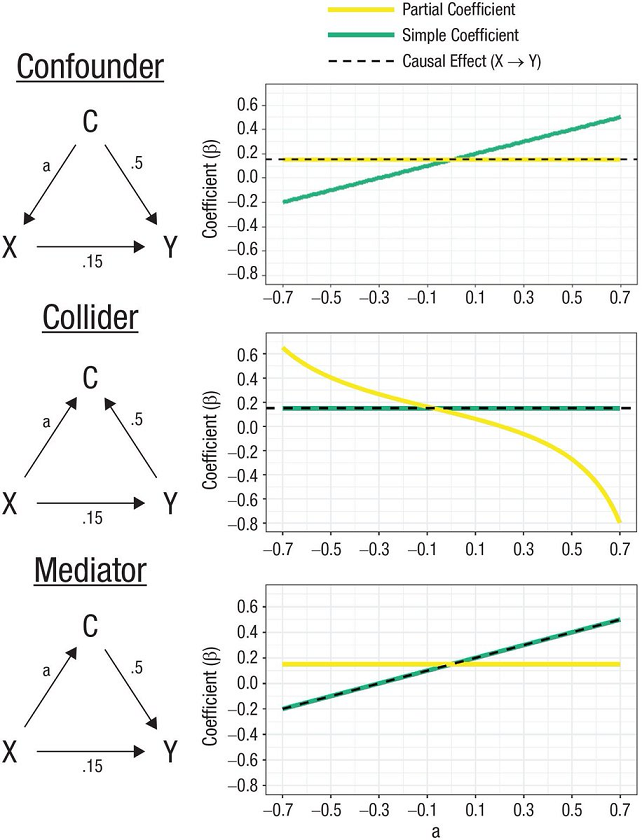

So this tweet came across my feed. It refers to this article, Statistical Control Requires Causal Justification by Wysocki, Lawson and Rhemtulla, published in June last year (2022) in Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. I was struck by the clarity of Figure 4 from that paper. It is such a great tool for at once explaining the difference between a confounder, collider and mediator and showing how they have different impacts on a regression; and hence lead to different decisions about whether to include the confounder, collider or mediator variable in the model. What I’m showing here isn’t the original, but my own version of it, which I’ll eventually come to describing how I did it later in this post:

Here is the original caption for Figure 4 from Wysocki et al:

“Partial and simple regression coefficients under three causal structures. In each graph, the x-axis depicts the population value of the direct effect that connects the control variable and the predictor (a), and the y-axis depicts the value of the regression coefficient of Y on X. The direct effect of X on Y and the value of the direct effect connecting Y and C are held constant across the results. Solid lines represent the partial (yellow line) and simple (green line) regression coefficients. The dashed line represents the total X → Y causal effect.”

The idea is that in all three cases we are interested in the degree to which X causes Y. A third variable C is also present and is correlated with both X and Y. Should we ‘control’ for it, ie include it as another variable on the right hand side of a regression? The answer is, it depends on whether C is a confounder, collider or mediator - and there will be no way to tell from your data which it is. So some kind of reasoning based on prior knowledge and theorising is required, or making (and documenting) some explicit assumptions. Some sciencing is required before you do the actual model specification and fitting.

The basic interpretation of these terms is as follows. For illustrative purposes I am going to use examples from a hypothetical situation where we want to understand the impact of education on income; that is, X is education and Y is income:

- C is a confounder if it impacts on both X and Y. For example, gender is known to lead to different education outcomes, and it also leads to differences in income in various complicated ways. Another example might be innate ability, if such a thing exists and could be measured. You want to control for confounders, because if you don’t include them in the regression, some of the coefficient in front of X is going to be picking up causal impacts that are really down to the confounder. In the chart on the right of the figure we see that the green ‘simple coefficient’ - the coefficient we’d estimate for X in a simple regression of Y ~ X - gets the wrong result. The correct value of the impact of X on Y is 0.15, and to get this you need the yellow ‘partial coefficient’ ie the coefficient for X you get when you control for C, in a regression of Y ~ X + C. How far out the simple coefficient is depends on the size of a, the causal effect of C on X; if a is zero then both methods get you the same answer

- C is a collider is when both X and Y impact on C, but it itself does not impact on either of them. I find it harder to think of pure examples of these, but in my case I’m going to use hobbies as one. The hobbies you’ve got definitely depend on what you were exposed to in your education; and whether you can afford them financially and timewise will depend on your income (in complicated ways). True, hobbies will also potentially impact on your income but I’m hoping (for purposes of illustration) in ways that are less important than the Y -> C part of the diagram here. You don’t want to control for colliders in a regression (see how the green ‘simple coefficient’ line correctly estimates the true causality of X -> Y, whereas the yellow ‘partial coefficient’ line doesn’t). The intuition for this is that because C doesn’t really impact on Y, when you include it in the regression some of the true impact of X on Y is falsely attributed to C just because of its correlation with both the important variables. (Side note - I’m not thrilled with the example of ‘hobbies’ here, but it serves the point. I also considered ‘suburb you live in’ and ‘sports team you support’, none of which are pefect either.)

- C is a mediator is when X causes C and C causes Y. A good example in our case could be occupation; your education has a big impact on your occupation, which in turn has a big impact on your income. You don’t want to control for a mediator if you are interested in the full effect of X on Y! Because a huge part of how X impacts on Y is precisely through the mediation of C, in our case choice of and access to occupation, given a certain level of education. If you ‘control’ for occupation you will be greatly underestimating the importance of education.

Incidentally this last point is behind one of the great perpetual culture war debates, whether to control for occupation and experience when estimating the gender pay gap. Much of the gender pay gap goes away when we do so, so does this mean there is no problem here? No, because occupation and experience are mediator variables which are precisely the means by which gender leads to a pay gap. By controlling for them you are missing out on the actual mechanism of precisely in what you are interested.

However there is a time when you might be interested in controlling for occupation and experience in a regression of pay gap on gender. This is when you are seeking to measure the direct impact, and only the direct impact, of gender in pay decisions - most likely in the context of gender discrimination at the final stage of remuneration determination. In this case, occupation and experience are no longer mediators, they are if anything confounders, because X is no longer “gender” but “gender discrimination in the current workplace making a pay decision” (for which we use actual, observed gender as a proxy). Now C impacts on Y and might impact on X. So if you want to estimate that final “equal pay for equal work” step of the chain then yes it is legitimate to control for occupation and experience. Just don’t mix this up with the total impact of gender on the pay gap, which is mediated through occupation and experience.

Simulating data

So I wanted to simulate this data fitting these three types of relationships, and re-create the original Figure 4 from Wysocki et al’s paper. I think this is pretty simple, so long as I am happy with getting the substance right and not matching exact details. First, I made three functions, one each for the situation where the nuisance variable is a confounder, collider or mediator.

In the code below I call the nuisance variable (which is C in the original diagrams) z to avoid creating a conflict with the C() or c() functions in R (this would be completely workable, but goes against highly ingrained habits on my part to not use frequently-used base R functions as names for other objects). Each of the three functions starts the data generation with the one variable that is exogenous to the system - isn’t causally impacted on by either of the other two. Then it uses that variable to generate the variable that is impacted on by the first variable, and then finally creates the final variable. Each variable has a standard (ie mean = 0, variance = 1) Gaussian randomness built in, and the relationship between variables has simple linear coefficients but no intercept terms. For example, in the confounder example, Y = b1.X + b2.C + noise.

Post continues after R code

# attempt to recreate Figure 4 from

# https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/25152459221095823

library(tidyverse)

library(ggdag)

library(patchwork)

#----------------simulating data-------------

# In the below I call a variable `z` that in the diagrams is called `C`

#' Simulate a 3 variable situation where a nuisance variable is a confounder

#'

#' @param zx coefficient for impact of z on x

#' @param xy coefficient for impact of x on y

#' @param zy coefficient for impact of z on y

#' @param n sample size

#' @param seed random seed set for reproducibility

#' @returns a tibble of three variables x, y and z. x causes y

#' and z is a confounder ie it impacts on both x and y

sim_confounder <- function(zx, xy = 0.15, zy = 0.5, n = 1000, seed = 123){

set.seed(seed)

z <- rnorm(n)

x <- zx * z + rnorm(n)

y <- xy * x + zy * z + rnorm(n)

return(tibble::tibble(x, y, z))

}

#' Simulate a 3 variable situation where a nuisance variable is a collider

#'

#' @param xz coefficient for impact of x on z

#' @param xy coefficient for impact of x on y

#' @param yz coefficient for impact of y on z

#' @param n sample size

#' @param seed random seed set for reproducibility

#' @returns a tibble of three variables x, y and z. x causes y

#' and z is a collider ie it is impacted on by both x and y

sim_collider <- function(xz, xy = 0.15, yz = 0.5, n = 1000, seed = 123){

set.seed(seed)

x <- rnorm(n)

y <- xy * x + rnorm(n)

z <- xz * x + yz * y + rnorm(n)

return(tibble::tibble(x, y, z))

}

#' Simulate a 3 variable situation where a nuisance variable is a mediator

#'

#' @param xz coefficient for impact of x on z

#' @param xy coefficient for impact of x on y

#' @param zy coefficient for impact of z on y

#' @param n sample size

#' @param seed random seed set for reproducibility

#' @returns a tibble of three variables x, y and z. x causes y

#' and z is a mediator ie x impacts on z and z impacts on y, so some of the

#' impact of x on y comes via z

sim_mediator <- function(xz, xy = 0.15, zy = 0.5, n = 1000, seed = 123){

set.seed(seed)

x <- rnorm(n)

z <- xz * x + rnorm(n)

y = xy * x + zy * z + rnorm(n)

return(tibble::tibble(x, y, z))

}The idea with these functions is that they work with multiple values of “a” (as per the original terminology of the diagrams). But for illustrative purposes we can use these functions to generate data where a=0.3 (a reasonably material relationship) and see how the correlations come out. This helps make it obvious that you can’t tell from the data alone (at least with this sort of snapshot, observational data) which way the causality is going:

> # Correlations of example different datasets:

> round(cor(sim_confounder(0.3, n = 10000)), 2)

x y z

x 1.00 0.26 0.29

y 0.26 1.00 0.49

z 0.29 0.49 1.00

> round(cor(sim_collider(0.3, n = 10000)), 2)

x y z

x 1.00 0.15 0.34

y 0.15 1.00 0.47

z 0.34 0.47 1.00

> round(cor(sim_mediator(0.3, n = 10000)), 2)

x y z

x 1.00 0.28 0.29

y 0.28 1.00 0.49

z 0.29 0.49 1.00

Basically the correlations tell us nothing about the direction of causality.

So my next step is to generate the data for many different values of a, for each of the three relationship types. There are plenty of ways to do this efficiently, here is mine. For those curious, res standards for “results”, in my object names. Naming things is hard!

At the end of the code below I have an object res which has values of a and estimates of the simple coefficient and partial coefficient in front of X (in the regression of Y on X) for that relationship type, as well as the true causal impact of X on Y.

Post continues after R code

#-----------generate data and fit regressions, for various values of a

the_a <- seq(from= -0.7, to = 0.7, length.out = 10)

the_n <- 10000

res_conf <- lapply(the_a, sim_confounder, n = the_n) |>

bind_rows() |>

mutate(a = rep(the_a, each = the_n),

var = "Confounder") |>

group_by(a, var) |>

summarise(`Simple coefficient` = coef(lm(y ~ x))[['x']],

`Partial coefficient` = coef(lm(y ~ x + z))[['x']],

`Causal effect` = 0.15)

res_coll <- lapply(the_a, sim_collider, n = the_n) |>

bind_rows() |>

mutate(a = rep(the_a, each = the_n),

var = "Collider") |>

group_by(a, var) |>

summarise(`Simple coefficient` = coef(lm(y ~ x))[['x']],

`Partial coefficient` = coef(lm(y ~ x + z))[['x']],

`Causal effect` = 0.15)

res_medi <- lapply(the_a, sim_mediator, n = the_n) |>

bind_rows() |>

mutate(a = rep(the_a, each = the_n),

var = "Mediator") |>

group_by(a, var) |>

summarise(`Simple coefficient` = coef(lm(y ~ x))[['x']],

`Partial coefficient` = coef(lm(y ~ x + z))[['x']],

`Causal effect` = `Simple coefficient`)

res <- bind_rows(res_conf, res_coll, res_medi) |>

ungroup()Drawing a plot of regression estimates

It only remains to draw and polish the chart, which is basic ggplot2 stuff. Probably the only noteworthy trick in the below is a slight improvement on the original diagram where I move the Y axis and its labels to the right of the chart, to avoid clutter near where I am going to place the DAGs in the end figure.

Post continues after R code

#------------------draw plot-------------------

the_font <- "Calibri"

tg <- guide_legend(direction = "vertical", keywidth = unit(3, "cm"))

p <- res |>

gather(method, coefficient, -a, -var) |>

mutate(method = fct_relevel(method, "Causal effect", after = Inf),

var = fct_relevel(var, "Confounder")) |>

mutate(method = fct_recode(method, "Causal effect (X causing Y)" = "Causal effect")) |>

ggplot(aes(x = a, y = coefficient, colour = method, linetype = method)) +

facet_wrap(~var, ncol = 1) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1.5) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(from = -0.7, to = 0.7, by = 0.2)) +

scale_y_continuous(position = "right") +

scale_linetype_manual(values = c(1, 1,2), guide = tg) +

scale_colour_manual(values = c("yellow", "lightgreen", "black"), guide = tg) +

labs(colour = "", linetype = "",

y = expression("Coefficient "~beta),

caption = "Reproducing (inexactly) a figure by Wysocki, Lawson and Rhemtulla in \n'Statistical Control Requires Causal Justification'. https:/freerangestats.info") +

theme_light(base_family = the_font) +

theme(plot.caption = element_text(colour = "grey50"),

strip.text = element_text(size = rel(1), face = "bold"),

legend.position = "top")Drawing Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs)

Next comes drawing the DAGs themselves. I’m not happy with how I’ve done this, but it works… The tricky part was getting labels in the edges connecting each node. This is possible (as indeed I do in the code below) but it involved using trial and error to work out which labels went with each connecting edge. I don’t like this at all! There must be a way to do this “properly” with mapping an aesthetic to some variable but I couldn’t work it out.

DAGs as drawn with ggdag seem to have a random orientation, so setting the seed below each time just before drawing a DAG is critical for having them all in the same orientation, with X and Y both at the bottom of the image.

Post continues after R code

#------------------draw DAGs---------------

arrow_col <- "grey70"

set.seed(123)

d1 <- dagify(

Y ~ X + C,

X ~ C

) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, xend = xend, yend = yend)) +

geom_dag_edges_fan(aes(label = c("a", 0.5, 0.15, NA)),

edge_colour = arrow_col,

label_colour = "black") +

geom_dag_text(colour = "black") +

theme_dag()

set.seed(123)

d2 <- dagify(

C ~ X + Y,

Y ~ X

) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, xend = xend, yend = yend)) +

geom_dag_edges_fan(aes(label = c(NA, "a", 0.15, 0.5)),

edge_colour = arrow_col,

label_colour = "black") +

geom_dag_text(colour = "black") +

theme_dag()

set.seed(123)

d3 <- dagify(

C ~ X,

Y ~ X + C

) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, xend = xend, yend = yend)) +

#geom_dag_point() +

geom_dag_edges_fan(aes(label = c(0.5, "a", 0.15, NA)),

edge_colour = arrow_col,

label_colour = "black") +

geom_dag_text(colour = "black") +

theme_dag()So that code defines the three DAGs in the objects d1, d2, d3 but doesn’t draw them.

Pulling the combined figure together

The final step is to use the magic of patchwork package by Thomas Pedersen to lay out the diagrams on the actual page. The design argument to plot_layout() lets you take total control of how multiple ggplot2 objects (in our case, p, d1, d2 and d3) are layed out in a figure, so I make use of that here.

Post continues after R code

design <- c(

area(1,1,2,2),

area(3,1,4,2),

area(5,1,6,2),

area(1,3,6,5)

)

print(d1 + d2 + d3 + p +

plot_layout(design = design) +

plot_annotation(title = "Statistical control requires causal justification",

subtitle = "Only when the variable is a confounder is it correct to 'control' for it in a regression.",

theme = theme(text = element_text(family = the_font)))

)Comparison

So as a reminder, here’s a repeat of the final image:

… and here’s the original version from Wysocki et al:

There’s an obvious difference! My “simple coefficient” for X in the presence of a confounder has a gentle S curve whereas their’s is a straight line; and their “partial coefficient” for X in the presence of a collider has a gentle S curve whereas mine is in a straight line. Why? I don’t know! Obviously it is to do with our different simulated data. Mine is generated as some simple linear relationships; their’s is described as:

“We used path tracing (i.e., Wright’s rules; Alwin & Hauser, 1975; see Appendix A for an example) to obtain a population correlation matrix for each causal structure and calculated regression coefficients from each population correlation matrix using the formula β=Σ−1xxΣxy, in which Σxx is the p×p correlation matrix of predictors and Σxy is a p×1 vector that contains correlations between each predictor and the outcome”

That’s clearly a bit different from what I did. I’m not going to delve into exactly why that makes the results a bit different. The difference doesn’t change the substantive point about how you can go wrong with the wrong choice of partial or simple coefficient (corresponding to whether you “control” for the nuisance variable or not).

That’s all folks. Remember not to include collider and mediator variables in your controls in a regression, at least when you are interested in causal explanations (predictions being something else again)!