The New York City Taxi & Limousine Commission’s open data of taxi trip records is rightly a go-to test piece for analytical methods for largish data. Check out, for example:

- The benchmark of interesting analysis is set by Todd W Schneider’s well-written and rightly famous blog post ‘Analyzing 1.1 Billion NYC Taxi and Uber Trips, with a Vengeance’, for which he used PostgreSQL, PostGIS and R

- Mark Litwintschik provides benchmarks of four different queries of the data on different software and hardware setups, mostly clusters of computers operating big data software such as BrytlytDB, MapD, Redshift, BigQuery and Spark (source code)

- Various providers use the data to show off the impressive speed of their ingest and analysis tools eg MemSQL or Ocean9

A week or so ago there was a flurry in my corner of the twitterverse with people responding to a great blog post by Jovan Veljanoski How to analyse 100 GB of data on your laptop with Python. Veljanoski is one of the co-founders of vaex.io. Vaex is a powerful Python library that empowers a data scientist with the convenient R-like DataFrame-based feel of Pandas for data that is too large to reside in memory.

The trick used by Vaex is that the data is stored on disk in the efficient HDF5 format. Vaex only uses the minimal scan of the dataset it needs for any particular action. So once Veljanoski has connected to the data, operations like simple summaries of the 1+ billion taxi ride observations he demonstrates on can be done lightning fast. The most impressive example given is an interactive heatmap of New York, which can go to the right part of the data so fast that the user gets the sort of performance with this 100+ GB dataset that normally is only possible when all the data is in RAM.

That’s genuinely impressive, but how necessary is Vaex to analyse this sort of data on commodity hardware? Veljanoski argues in his post that “There are three strategies commonly employed when working with such datasets” :

- sub-sample the data

- distributed computing

- a single strong cloud instance with as much memory as required

As he points out, each of these comes with its disadvantages. But there’s a glaring omission from the list - use a database! A good old-fashioned relational database management system is the tool invented for this sort of data, and today’s database software is the highly optimised beneficiary of untold billions of dollars of investment from firms like IBM, Oracle and Microsoft (for example, Oracle alone spends about $6 billion per year on research and development). Schneider’s post showed that open source relational database technology (PostgreSQL) is more than up to the job. In fact, a number of the features of Vaex showcased in Veljanoski’s blog post sound almost like a re-invention of some aspects of the database approach:

- data held on disk can be inspected a few rows at once without loading it all into memory;

- the management system holds key metadata or indexes that let certain kinds of simpler analysis be performed via radical shortcuts;

- virtual views of the data can be created instantly as filtered subsets or with additional calculated columns, without copying the whole dataset.

So out of curiousity I set out to see how the data can be handled by my unremarkable personal laptop and the software toolkit I most commonly use at the moment - R in combination with Microsoft SQL Server (which I chose because it’s my most common database in work contexts, has a free developer edition, and has powerful columnstore indexes which I think will help handle this sized data).

What did I find?

- Even relatively tidy data is serious work to prepare for analysis - whether the prep is an extract-transform-load to a database, or conversion to HDF5.

- The combination of a standard laptop, SQL Server (or other powerful database tool) and R is fine for dealing with data of several hundred gigabytes in size, but I would want a bigger computer and a large fast solid state drive for much bigger than this.

- Most analysis on this sort of data has aggregation and summary operations as its first step, so by the time you hit a statistical model or a graphic you are likely working with a much smaller dataset than the original.

- Most of the interesting things to say about the NYC taxi data have already been said.

Let’s see how that works out.

Data preparation

“80% of data scientists’ work is managing, tidying and cleaning data. And most of the other 20% is complaining about it.”

Source : I wouldn’t know where to start to find who said this first.

The original taxicab data can be downloaded, one CSV file per month, from the New York City Taxi & Limousine Commission’s website. The data are available to 2019, but the data model changed several times, and by the second half of 2016 latitude and longitude were not being reported as per the earlier detail, probably for belated privacy reasons. If you’re interested you can see the full load process in my GitHub repo. You could also see Todd W Schneider’s PostgreSQL and R version which I suspect is better managed.

Unfortunately Veljanoski’s post doesn’t link to the code he used to process the original CSVs into HDF5 format. His Jupyter notebook starts on the basis the data is available in HDF5 format on your laptop. He links to example code for converting CSVs to HDF5 but a) it’s for a different dataset and b) it’s clear the task is non-trivial.

So I can’t directly compare his process to mine, but I can say that the load process with my toolkit was a significant effort. The contributing factors to this were:

- irrespective of software choices, the data are large for the hardware I’m using them for, which leads to sub-optimal workarounds. For example, my hard drive isn’t large enough to store at the same time all the original CSVs, a staging copy of the data in the database, and the final analysis-ready copy of the data. This meant I had to delete the CSVs as my transformation process was going; and if I found a problem (as happened several times) I had to repeat some or all of the original downloads (which takes 6+ hours even on my fast-by-Australian-standards 100+ MBPS interent connection).

- the data model changes several times. For example, there are half a dozen different sets of column names, sometimes varying by just capitalisation, sometimes by name changes such as

trip_pickup_datetimebecomingtpep_pickup_datetime. There is quite a good user guide available but I foolishly didn’t look for it early enough. The data dictionary is for the latest data model; there might be historical versions but I didn’t look hard enough to find them. - some of the data is corrupt (eg some of the monthly CSVs in 2010 have several thousand rows with more columns in them than the other rows) - a relatively small amount, but enough to cause problems in combination with the other factors.

In the second half of 2016 something happened to the data I couldn’t understand, and this in combination with the fact that latitude and longitude are no longer recorded led me to give up at that point and confine my analysis to the first 7.5 years. At well over 200GB of CSVs this still seems an adequate test.

I would say I spent at least eight hours of effort over two weeks of calendar time on the extract-transform-load of the CSVs into their eventual form in the database, and I am far from satisfied with the result; I think another person day or three is needed to tidy it up, better document it, and introduce some efficiencies and performance enhancements. The two weeks of calendar time is significant too - because a number of the operations took multiple hours to run it was common to have to let it run and then go do something else (eg sleep, walk around the park, go do my real job, etc) - resulting in task switching costs when I came back to this project several days later, and meaning that even if I had devoted three full time days to the project I wouldn’t have been able to use them efficiently. The physical bottlenecks, ordered from most to least, were writing and reading to my slow physical disk (the only drive I had with space for this data); downloading large data over the internet; and processing.

But ultimately I got a working version of the data I’m fairly happy with. In the database it looks like this:

I’m satisfied its more analysis-ready than some of the alternative loads of this data I’ve seen out there. For example, I have all the codes built in to the database; no need to look up elsewhere that payment type 1 is cash, 2 is credit, etc. Plus my loading process standardises the different versions of vendor coding that are used - sometimes “1” and “2”, sometimes “CMT”, “VTS” and “DDS” (which seemed to disappear early in the series and isn’t listed in the data dictionary). To give an idea of what this means in terms of code development, here is one step in the overall process. This chunk of SQL code takes data from a staging table - dbo.tripdata_0914, with the raw data from the first six years when the column sequencing (but not names or coding) was consistent - and loads it into the evental target table tripdata in the yellow schema:

-- First six years, with no surcharge data:

INSERT INTO yellow.tripdata(

vendor_code,

trip_pickup_datetime,

trip_dropoff_datetime,

passenger_count,

trip_distance,

start_lon,

start_lat,

rate_code,

store_and_forward_code,

end_lon,

end_lat,

payment_type_code,

fare_amt,

extra,

mta_tax,

tip_amt,

tolls_amt,

total_amt

)

SELECT

CASE

WHEN vendor_name = '1' THEN 'CMT'

WHEN vendor_name = '2' THEN 'VTS'

ELSE vendor_name

END,

trip_pickup_datetime,

trip_dropoff_datetime,

passenger_count,

TRY_CAST(trip_distance AS DECIMAL(9, 4)),

TRY_CAST(start_lon AS DECIMAL(9, 6)),

TRY_CAST(start_lat AS DECIMAL(9, 6)),

CASE

WHEN rate_code IN (1,2,3,4,5,6) THEN rate_code

ELSE NULL

END,

CASE

WHEN store_and_forward IN ('0', 'FALSE', 'N') THEN 'N'

WHEN store_and_forward IN ('1', 'TRUE', 'Y') THEN 'Y'

END,

TRY_CAST(end_lon AS DECIMAL(9, 6)),

TRY_CAST(end_lat AS DECIMAL(9, 6)),

CASE

WHEN payment_type IN ('credit', 'cre', '1') THEN 1

WHEN payment_type IN ('cash', 'csh', 'cas', '2') THEN 2

WHEN payment_type IN ('no', 'no charge', 'noc', '3') THEN 3

WHEN payment_type IN ('disput', 'dis', '4') THEN 4

WHEN payment_type IN ('unknown', 'unk', '5') THEN 5

WHEN payment_type In ('voided trip', 'voi', 'voided', '6') THEN 6

ELSE NULL

END,

TRY_CAST(fare_amt AS DECIMAL(9, 2)),

TRY_CAST(surcharge AS DECIMAL(9, 2)),

TRY_CAST(mta_tax AS DECIMAL(9, 2)),

TRY_CAST(tip_amt AS DECIMAL(9, 2)),

TRY_CAST(tolls_amt AS DECIMAL(9, 2)),

TRY_CAST(total_amt AS DECIMAL(9, 2))

FROM dbo.tripdata_0914You can see that I also handle issues such as the inconsistent coding of “payment type”, and cut down the storage size of various numeric variables. For example, trip_distance was loaded into my staging table as 15 digit precision floating point data which takes up 8 bytes of space per observation; reducing this to DECIMAL(9, 4) saves three bytes per row of the data while still allowing plenty of range and precision - numbers of the format 99999.1234. Three bytes per row adds up materially over 1+ billion rows. The TRY_CAST() functions are needed because many of these numeric variables have physically impossible values (eg longitudes with four or more digits left of the decimal point) which cause numeric overflow errors otherwise.

It’s easy to see where that eight hours went… In contrast, I would say I have spent about four hours on analysis of any sort (mostly descriptive) and four hours on writing up this post. So the “80%” of time spent on data cleaning isn’t quite right here - more like 50%. Noting that in this case, the data is exceptionally clean and tidy already - other than having direct access to a well-maintained warehouse, one will rarely get data as nicely released by the NYC Taxi & Limousine Commission.

On the other hand, there’s big economies of scale here. If I did another couple of blog posts on this data, that 50% or so of effort that was on data preparation would pretty quickly go down. Worth noting.

With one of SQL Server’s powerful, fast clustered columnstore indexes on the main table, the total data size on disk is about 45 GB for main data and another 33 GB for an unclustered primary key identifying each row which I think is probably not needed and could be dropped. That 45GB is a lot of compression from the original size of more than 200GB, but more importantly the columnstore approach makes analysis pretty fast for dealing with 1.2+ billion rows even on my poor underpowered laptop and its old-school mechanical hard disk drive.

Repeating previous analysis - maps and variable distribution

Passenger counts distribution

So, let’s see what I can do now that the data’s ready. I repeated the first few bits of exploratory analysis from Veljanoski’s article. For example, here is R code to set up an analytical session and explore the distribution of “number of passengers” on each trip:

library(tidyverse)

library(scales)

library(odbc)

library(DBI)

library(clipr)

library(knitr)

library(kableExtra)

library(ggmap)

library(Cairo)

# assumes you have an ODBC data source named "nyc_taxi" to the database created by https://github.com/ellisp/nyc-taxis:

nyc_taxi <- dbConnect(odbc(), "localhost", database = "nyc_taxi")

#' Theme for dark background maps to be used later

#'

#' @author minimally adapted from a Todd Schneider original

theme_dark_map <- function(base_size = 12, font_family = "Sans"){

theme_bw(base_size) +

theme(text = element_text(family = font_family, color = "#ffffff"),

rect = element_rect(fill = "#000000", color = "#000000"),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#000000", color = "#000000"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#000000", color = "#000000"),

plot.title = element_text(family = font_family),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

panel.border = element_blank(),

axis.text = element_blank(),

axis.title = element_blank(),

axis.ticks = element_blank())

}

theme_white_map <- function(base_size = 12, font_family = main_font){

theme_bw(base_size) +

theme(text = element_text(family = font_family, color = "#000000"),

rect = element_rect(fill = "#ffffff", color = "#ffffff"),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#ffffff", color = "#ffffff"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#ffffff", color = "#ffffff"),

plot.title = element_text(family = font_family),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

panel.border = element_blank(),

axis.text = element_blank(),

axis.title = element_blank(),

axis.ticks = element_blank(),

plot.caption = element_text(color = "grey50"))

}

the_caption <- "Analysis by https:/freerangestats.info with data from NYC Taxi & Limousine Commission"

#-----------------------passenger count frequencies------

sql <- "

SELECT

COUNT(1) AS freq,

passenger_count

FROM yellow.tripdata

GROUP BY passenger_count

"

# takes a couple of seconds:

pc_freq <- dbGetQuery(nyc_taxi, sql)

pc_freq %>%

ggplot(aes(x = str_pad(passenger_count, 3, pad = "0"), y = freq)) +

geom_col() +

scale_y_log10(label = comma) +

scale_x_discrete(labels = sort(unique(pc_freq$passenger_count))) +

labs(x = "Number of passengers (discrete scale - only values with at least one trip shown)",

y = "Number of trips (log scale)",

title = "Number of passengers per trip",

subtitle = "New York City yellow cabs January 2009 to mid 2016",

caption = the_caption)This produces the following image for us, very similar to Veljanoski original. It’s not identical because I’ve got six months more data and I’ve built more data-cleaning into my ETL - most notably where the number of trip passengers is zero I have replaced this with NULL in my database.

My code took less than five seconds to run in contrast to his 23 seconds with Vaex/Python, so I’m pretty pleased by performance so far.

Trip distance distribution

A very similar bit of SQL and R code gives us a similar plot for distribution of trip distance in miles, truncated at just those less than 250 miles. Because the trip distances are continuous variables, to show their distribution I’m going to need to do some kind of summary. With smaller data I would put all the observations into R and use geom_density() to do the work, but as this would mean transferring a billion observations from the database to R’s environment for little gain, I opt to round the distances to the nearest tenth of a mile and aggregate them. In effect, I’m building my own fixed-bin-width histogram. Here’s my first go at that:

…produced with:

#-----------------------distance in miles--------------

sql <- "

SELECT

COUNT(1) AS freq,

ROUND(trip_distance, 1) AS trip_distance

FROM yellow.tripdata

GROUP BY ROUND(trip_distance, 1)

"

# takes about 20 seconds

td_freq <- dbGetQuery(nyc_taxi, sql)

td_freq %>%

filter(trip_distance <= 250) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = trip_distance, y = freq)) +

geom_line() +

scale_y_log10(label = comma) +

labs(x = "Trip distance in miles - rounded to 0.1 of a mile",

y = "Number of trips (log scale)",

title = "Trip distances",

subtitle = "New York City yellow cabs January 2009 to mid 2016",

caption = the_caption)This looked quite markedly different from Veljanoski’s original so I tried rounding to the nearest mile rather than tenth of a mile and got this result (code not shown):

Either of these charts gives a good indication of what is happening, but the second is probably better. We see a suspiciously marked drop-off in distances at exactly 100 miles, which is almost certainly measurement error rather than a physical reality.

This time, my database was much slower than Valjanoski’s Vaex/Python combination - 20 seconds versus one second.

Maps

Todd Schneider’s ground-breaking post with this data was conspicuous because of the beauty of his clean high resolution images of pickups and drop off points. He wrote “These maps show every taxi pickup and drop off, respectively, in New York City from 2009-2015. The maps are made up of tiny dots, where brighter regions indicate more taxi activity.”

In fact, while the maps do indeed “show” every pickup and drop off, a moments reflection would show that it isn’t physically possible to each individual trip to get its own blob of light. His 10MB high resolution images are 2,880 by 4,068 pixels in size, about 12 million pixels each. There are nearly 100 times as many trips as pixels, so some summary is required. In fact, in lines 200-230 of his SQL source code prepping for these maps we see how he is doing his - he rounds the latitude and longitude of each point to four decimal places and groups by this rounded location. Effectively he creates a fine grid across the New York City area and returns the average number of trips on each point of his grid.

This approach is fine (in fact I had done it myself even before looking at his source code) - I’m just mentioning it to highlight that when dealing with large datasets of this sort, to visualise them meaningfully you need to somehow reduce the size of the data in a meaningful way first before rendering them on the screen.

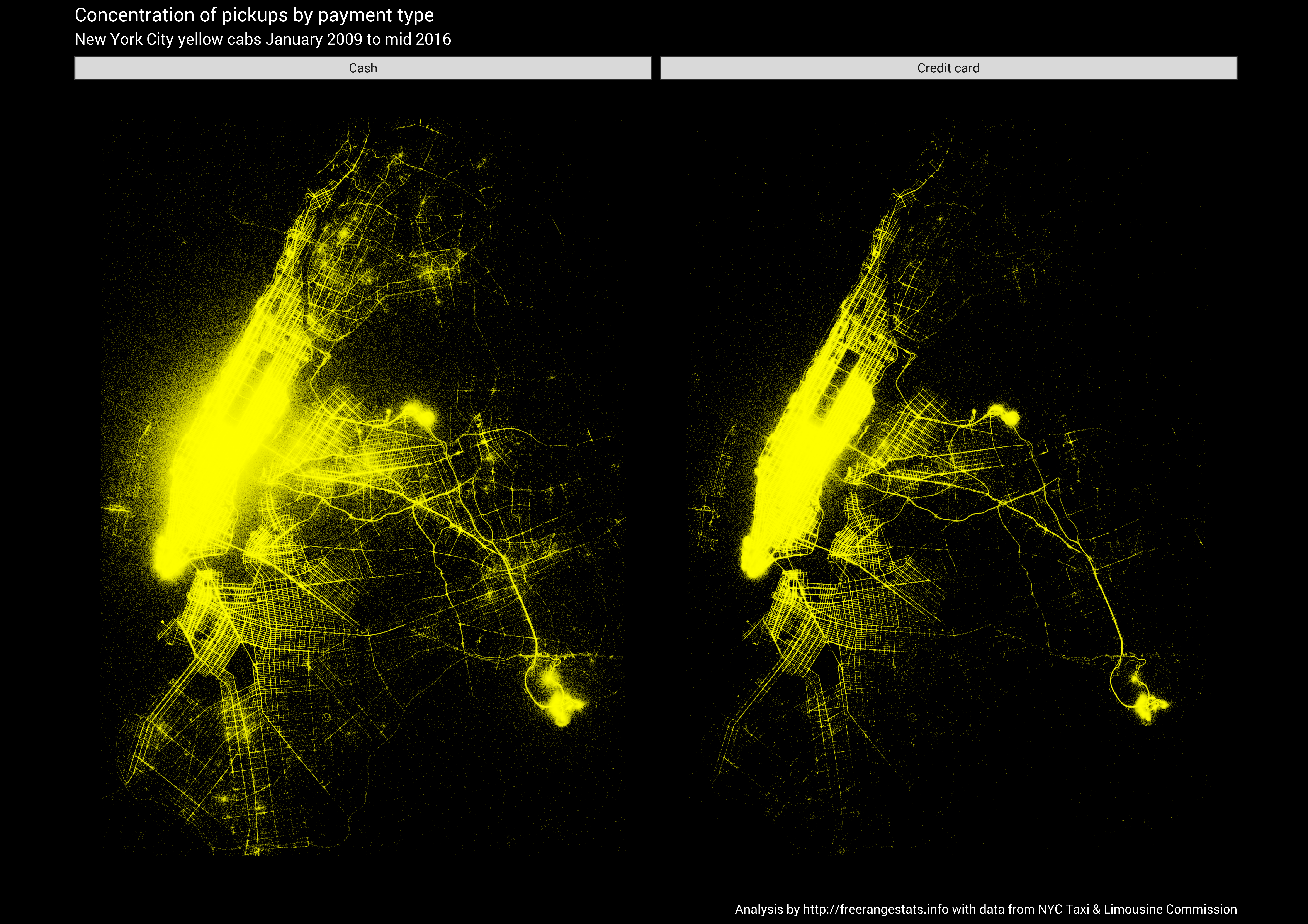

Let’s have a go at something similar. Here’s a map showing the pickup points of taxis from 2009 to mid 2016, split into payment by cash or by credit card

It’s not as polished as Schneider’s original, which I think was enhanced by using GIS methods to remove some of the noise from locations that were in the water. But it’s certainly a nice start.

Performance for producing this charts was acceptable but not that pleasant: about 10 minutes to summarise the data and 4 or 5 to render the graphic. In contrast Veljanoski with Vaex did something of similar complexity at the mid point of his post with about 60 seconds of elapsed time. That’s extremely impressive.

The time element

Let’s look at ways of looking at our data that takes into account the element of time - particularly periodicity. I might come back to this later as the data is a nice example of multiple seasonalities in a time series. If we aggregate it by hour we have at least three seasonal patterns - hours in the day, days in the week, and the annual cycle.

Again, we need some kind of aggregation before the billion taxi rides can be assimilated by the human eye. If we aggregate it up by hour it is still too dense to take in:

That’s the level of temporal granularity I’d like to analyse this when I’ve got more time but it’s too much for the eye.

If we aggregate up to months we have lost most of the interest, but it’s still a useful starting point. Note how the rides per hour declines substantially over time as more competition came in:

There’s a notable dip in taxi rides each winter.

Most other blogs draw some day-of-week by hour-of-day heatmaps at this point, and there’s good reason to - they’re a great summary of this sort of data. Here’s the most obvious one to draw - pure frequency of the start of taxi trips:

All that yellow in the top right shows (unsuprisingly) more taxi activity in evenings, and on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday rather than earlier in the week.

Here’s a replication of one of Veljanoski’s plots, showing the differing average fare collected per mile travelled at different times

Shorter taxi rides have a higher fare per mile, and I suspect we get more short taxi rides in during working hours on working days, which would explain the yellow highlight in the middle of that chart.

This analysis was easy to write with my database, but the performance was slower than Veljanoski’s (while still being totally acceptable). Whether this is due to my slow disk drive or software differences I’m not sure. Here’s the code for that data extract and analysis:

#--------------hour, week, year------------

# aggregate some summary data at hourly level

sql <- "

WITH a AS

(SELECT

trip_distance,

fare_amt,

YEAR(trip_pickup_datetime) AS yy,

DATEPART(hh, trip_pickup_datetime) AS hd,

DATEPART(dy, trip_pickup_datetime) AS dy,

DATEPART(dw, trip_pickup_datetime) AS dw,

DATEPART(m, trip_pickup_datetime) AS my

FROM yellow.tripdata

WHERE trip_distance > 0 AND total_amt > 0)

SELECT

COUNT(1) AS freq,

AVG(fare_amt / trip_distance) AS fare_per_mile,

yy, hd, dy, dw, my

FROM a

GROUP BY yy, hd, dy, dw, my

ORDER BY yy, dy, hd"

pickup_ts <- dbGetQuery(nyc_taxi, sql) %>% as_tibble()

# Note that weekday = 1 means sunday

# Hourly time series

pickup_ts %>%

mutate(meta_hour = 1:n()) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = meta_hour, y = freq, colour = as.ordered(my))) +

facet_wrap(~yy, scales = "free_x") +

geom_line() +

scale_colour_viridis_d(breaks = 1:12, labels = month.abb,

guide = guide_legend(ncol = 2)) +

scale_y_continuous(label = comma) +

labs(x = "Day of the year",

y = "Number of taxi pickups",

colour = "",

caption = the_caption,

title = "Taxi pickups time series",

subtitle = "Hourly observations 2009 to mid 2016") +

theme(legend.position = c(0.85, 0.15))

# Monthly time series

pickup_ts %>%

group_by(yy, my) %>%

summarise(freq = mean(freq)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = my, y = freq)) +

facet_wrap(~yy) +

geom_line() +

scale_y_continuous(label = comma) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 1:12, labels = month.abb) +

labs(x = "",

y = "Average hourly taxi pickups\n",

caption = the_caption,

title = "Taxi pickups time series",

subtitle = "Monthly averages based on hourly observations 2009 to mid 2016") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank())

# Heatmap of frequency of trips

# add a labelled day of the week variable, still keeping the ordering

pickup_ts2 <- pickup_ts %>%

mutate(dwl = factor(dw, labels = c("Sun", "Mon", "Tue", "Wed", "Thur", "Fri", "Sat")))

pickup_ts2 %>%

group_by(dwl, hd) %>%

summarise(freq = mean(freq)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = as.factor(hd), y = dwl, fill = freq)) +

geom_tile() +

scale_fill_viridis_c(label = comma) +

labs(caption = the_caption,

x = "Hour of the day",

y = "Day of the week",

title = "Taxi frequency by time of day and day of week",

subtitle = "Hourly observations from 2009 to mid 2016",

fill = "Pickups\nper hour")+

theme(legend.position = "right")

# Heatmap of average fare per distance

pickup_ts2 %>%

group_by(dwl, hd) %>%

summarise(fare_per_mile = sum(fare_per_mile * freq) / sum(freq)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = as.factor(hd), y = dwl, fill = fare_per_mile)) +

geom_tile() +

scale_fill_viridis_c(label = dollar) +

labs(caption = the_caption,

x = "Hour of the day",

y = "Day of the week",

title = "Taxi fare per distance by time of day and day of week",

subtitle = "Hourly observations from 2009 to mid 2016",

fill = "fare\nper mile") +

theme(legend.position = "right")Modelling average fare

Finally, I wanted to go beyond simple exploratory analysis to at least touch on some statistical modelling. I’ve only time for a taster here (both in terms of my writing time, and wondering if any readers will get this far…). I thought I’d start with a simple statistical model layer over some of the spatial charts I’d been playing with. So here’s a contour map (in the style of a weather forecast) showing average fare to be expected by location. While it’s not as beautiful as some of the high res point maps we’ve seen with this data, it’s probably more useful in terms of helping understand a fairly complex phenomenon:

It’s a nice illustration of how, even in primarily exploratory analysis, a statistical model can be powerful for helping shape thinking. In this case, the model is a generalized additive model, fit to the data by the mgcv::bam function which is optimised for working with larger data. I commonly use a generalized additive model with a smoother over latitude and longitude (think a rubbery sheet in three dimensional space) as a way of dealing with spatially correlated data.

In this case, rather than fit the model to the original individual trip data I’ve taken average fares over a grid of about 100,000 observations and used that data, weighted by the number of observations at each point, to train my simple model. Here’s this final bit of code for this analysis:

#-------------Modelling average fare by space-------------------

# extract data

sql <- "

SELECT

AVG(fare_amt) AS fare_amt,

COUNT(1) AS freq,

ROUND(start_lon, 3) AS start_lon,

ROUND(start_lat, 3) AS start_lat

FROM yellow.tripdata

WHERE fare_amt IS NOT NULL AND

start_lon > -74.05 AND start_lon < -73.75 AND

start_lat > 40.58 AND start_lat < 40.90 AND

end_lon > -74.05 AND end_lon < -73.75 AND

end_lat > 40.58 AND end_lat < 40.90 AND

passenger_count > 0 AND passenger_count < 7 AND

trip_distance > 0 AND trip_distance < 100

GROUP BY

ROUND(start_lon, 3),

ROUND(start_lat, 3)"

fare_rounded <- dbGetQuery(nyc_taxi, sql) # takes a while - 10 minutes or so

# about 95,000 observations

# Fit model

model <- bam(fare_amt ~ s(start_lon, start_lat), weights = freq, data = fare_rounded)

# predict values over a regular grid

all_lons <-seq(from = -74.05, to = -73.75, length.out = 200)

all_lats <- seq(from = 40.58, to = 40.90, length.out = 200)

the_grid <- expand.grid(

start_lon = all_lons,

start_lat = all_lats

)

predicted <- predict.bam(model, newdata = the_grid)

d <- the_grid %>%

as_tibble() %>%

mutate(predicted_fare = predicted) %>%

filter(start_lat < 40.8)

# get a background map

nyc_map <- ggmap::get_stamenmap(bbox = c(-74.05, 40.58,

-73.75, 40.80),

maptype = "toner-background")

# draw a contour map over that background:

ggmap(nyc_map) +

geom_raster(data = d,aes(x = start_lon,

y = start_lat,

fill = predicted_fare), alpha = 0.6) +

geom_contour(data = d, aes(x = start_lon,

y = start_lat,

z = predicted_fare)) +

geom_text_contour(data = d, aes(x = start_lon,

y = start_lat,

z = predicted_fare),

colour = "white") +

theme_white_map() +

scale_fill_viridis_c(option = "A", label = dollar) +

# we need cartesian coordinates because of raster. Probably better ways to fix this:

coord_cartesian() +

labs(title = "Expected taxi fare by pick-up point in New York",

subtitle = "New York City yellow cabs January 2009 to mid 2016",

caption = paste(the_caption,

"Map tiles by Stamen Design, under CC BY 3.0. Data by OpenStreetMap, under ODbL.",

sep = "\n"),

fill = "Predicted\naverage fare")It would be easy to extend this by looking for different spatial patterns (for example) by vendor, payment type, etc., but I’m lacking any particular motivation for that one. For now, I’m happy to conclude that my hardware and software is totally adequate for analysing this size data and I feel I’ve answered the implicit challenge of the “how to analyse 100s of GBs of data on your laptop with Python” blog post from a few week’s back. But I’ll need a bigger hard drive (or, more sensibly, to move to the cloud) if I do anything much bigger than this.