Today’s post comes from an idea and some starting code by my colleague David Diviny from Nous Group.

A common real-world problem is trying to estimate an unknown continuous variable from data that has been published in lumped-together bins. Often this will have been done for confidentialisation reasons; or it might just be that it has been aggregated that way for reporting and the original data is unavailable; or the binning might have happened at the time of measurement (common in surveys, when respondents might be asked to pick from several categories for ‘how often do you…’ or a similar question).

This is a related problem to the question of data being suppressed in low-count cells I discussed in some previous posts. It exemplifies a more general problem with censoring of all of our data into rough left and right bounds, at the mercy of the analyst who produced the original set of bins for publication.

Simulated data

I’m going to start with a made up but realistic example where respondents were asked “how long do you think it will take for X to happen”. Our simulated data from 10,000 responses (ok, perhaps that sample size isn’t very realistic for this sort of question :)) looks like this:

| bin | freq |

|---|---|

| <10 | 474 |

| 10-50 | 1710 |

| 50-100 | 1731 |

| 100 - 1000 | 6025 |

| >= 1000 | 60 |

Under the hood, I generated 10,000 actual continuous values from an exponential distribution, so I know the true un-binned values, the population mean and even the true data generating process. The true mean is 200.

A tempting but overly simplistic way of estimating the average time would be to allocate to each value the mid point of its bin; so we would have 474 values of 5, 1,710 values of 30, 1,731 of 75, and so on. This would give us an estimated population average of 358, far too high. The fact that I chose a very right-skewed distribution (exponential) to generate the data is the main reason this method doesn’t work, but this is not an unlikely scenario.

A vastly better method of estimating the mean is to model the underlying distribution, choosing parameters for it that are most likely to have generated the binned results we see. I could cheat and fit an exponential distribution, but let’s be more realistic and allow our model the flexibility of a Gamma distribution (of which exponential is a special case), reflecting the uncertainty we would have in encountering this data in the wild. Fitting this method to my binned data gives me a Gamma distribution with an estimated shape parameter of 1.02 (very close to the true data generating process value of 1, meaning a pure exponential distribution), estimated rate of 0.0051 and inferred mean of 198.5 - very close to the true total and much better than 358.

Here’s the results:

> # overall fit:

> summary(fitted_distribution_gamma)

Fitting of the distribution ' gamma ' By maximum likelihood on censored data

Parameters

estimate Std. Error

shape 1.01844011 0.0144237671

rate 0.00512979 0.0001093316

Loglikelihood: -10860.99 AIC: 21725.99 BIC: 21740.41

Correlation matrix:

shape rate

shape 1.0000000 0.7996524

rate 0.7996524 1.0000000

>

> # estimated mean

> fitted_distribution_gamma$estimate["shape"] / fitted_distribution_gamma$estimate["rate"]

shape

198.5345

And here’s the code that generated it. Most of this is just simulating the data; as is often the case, the actual statistical modelling here is a one liner, using the fitdistcens function from Marie Laure Delignette-Muller, Christophe Dutang (2015). fitdistrplus: An R Package for Fitting Distributions. Journal of Statistical Software, 64(4), 1-34. URL http://www.jstatsoft.org/v64/i04/

Post continues after R code

library(tidyverse)

library(multidplyr)

library(frs)

library(fitdistrplus)

library(knitr)

library(readxl)

library(kableExtra)

library(clipr)

#-----------------simulated data-------------

set.seed(123)

simulated_rate <- 0.005

volumes <- tibble(volume = rexp(n = 10000, rate = simulated_rate))

volumes <- volumes %>%

mutate(bin = case_when(volume < 10 ~ "<10",

volume < 50 ~ "10-50",

volume < 100 ~ "50-100",

volume < 1000 ~ "100 - 1000",

TRUE ~ ">= 1000"),

left = case_when(volume < 10 ~ 0,

volume < 50 ~ 10,

volume < 100 ~ 50,

volume < 1000 ~ 100,

TRUE ~ 1000),

right = case_when(volume < 10 ~ 10,

volume < 50 ~ 50,

volume < 100 ~ 100,

volume < 1000 ~ 1000,

TRUE ~ NA_real_),

bin = factor(bin, levels = c("<10", "10-50", "50-100", "100 - 1000", ">= 1000"), ordered = T))

# This is how it would look to the original user

volumes %>%

group_by(bin) %>%

summarise(freq = n())

# Create data frame with just "left" and "right" columns, one row per respondent, ready for fitdistcens

volumes_bin <- dplyr::select(volumes, left, right) %>%

as.data.frame()

# Fit model

fitted_distribution_gamma <- fitdistcens(volumes_bin, "gamma", start = list(rate = 0.01, shape = 1.5))

# overall fit:

summary(fitted_distribution_gamma)

# estimated mean

fitted_distribution_gamma$estimate["shape"] / fitted_distribution_gamma$estimate["rate"]

ggplot(volumes) +

geom_density(aes(x = volume)) +

stat_function(fun = dgamma, args = fitted_distribution_gamma$estimate, colour = "blue") +

annotate("text", x = 700, y = 0.0027, label = "Blue line shows modelled distribution; black is density of the actual data.")

# bin_based_mean (358 - very wrong)

volumes %>%

mutate(mid = (left + replace_na(right, 2000)) / 2) %>%

summarise(crude_mean = mean(mid)) %>%

pull(crude_mean)Here’s the comparison of our fitted distribution compared to the actual density of the data:

Binned data in the wild

Motivation - estimating average firm size from binned data

That’s all very well for simulated data, with an impressive reduction in error (from > 75% down to <1%), but did I cook the example by using a right-skewed distribution? Let’s use an even more realistic example, this time with real data.

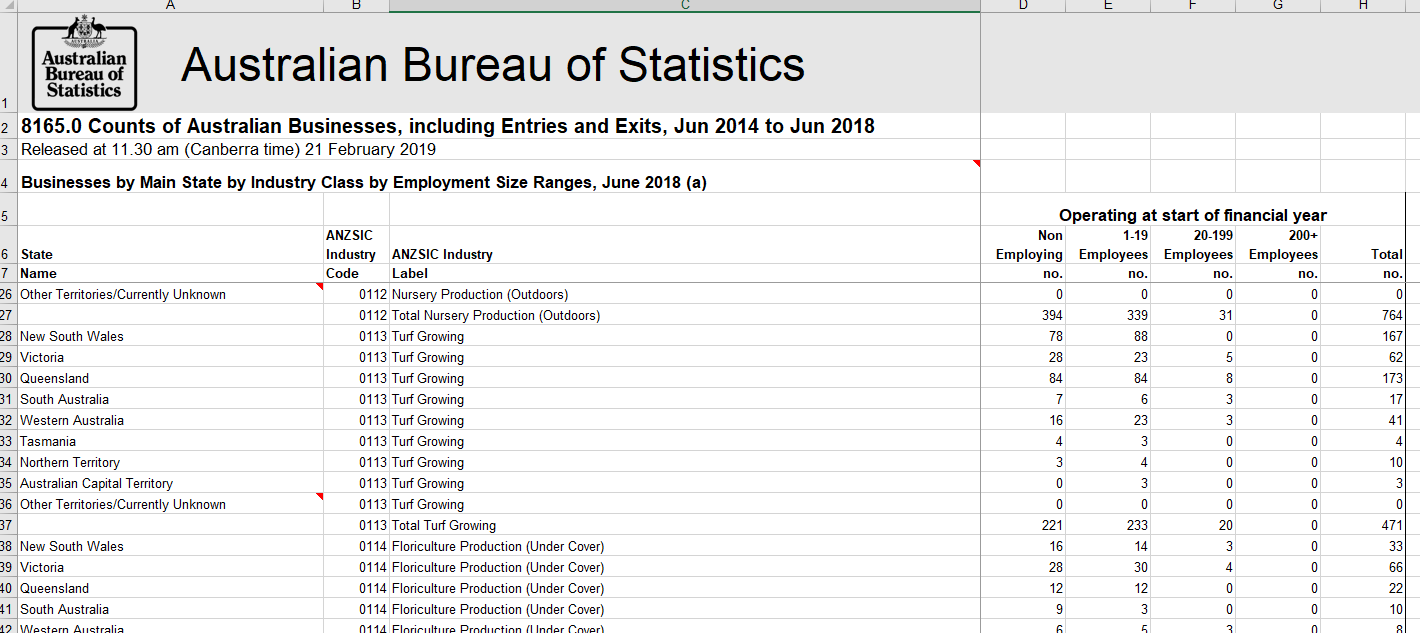

The Australian Bureau of Statistics series 8165.0 is the Count of Australian Businesses, including Entries and Exits. It includes a detailed breakdown of number of firms by primary state of the firm’s operation, number of employees (who may not all be in that state of course) and detailed industry classification. To preserve confidentiality the number of employees is reported in bins of 0, 1-19, 20-199 and 200+. The data looks like this:

For today’s purpose I am using the number of businesses operating at the start of the 2018 financial year, ie in July 2017.

If we want to use this data to estimate the mean number of employees per firm by industry and state we have a challenge that is almost identical to that with my simulated data, albeit we now have 4,473 instances of that challenge (one for each combination of industry and state or territory). So this is a good chance to see whether we can scale up this method to a larger and more complex dataset. Luckily, dplyr makes quick work of this sort of calculation, as we will see in a minute.

Data wrangling

The first job is tidy the data into a structure we want. The four digit industry classification is too detailed to be interesting for me just now and I will want to roll it up to three digit, and also be able to easily summarise it at even coarser levels for graphics. For some reason, the ANZSIC classification is surprisingly hard to get hold of in tidy format, so I’ve included it as the object d_anzsic_4_abs in my package of R miscellanea, frs (available via GitHub).

For fitting my distributions to censored data down the track, I need columns for the left and right bounds of each bin and the frequency of occurances in each. After tidying, the data looks like this:

| anzsic_group_code | anzsic_group | state | employees | left | right | division | freq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 011 | Nursery and Floriculture Production | Australian Capital Territory | 200-30000 | 200 | 30000 | Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 0 |

| 011 | Nursery and Floriculture Production | Australian Capital Territory | 20-199 | 20 | 199 | Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 0 |

| 011 | Nursery and Floriculture Production | Australian Capital Territory | 1-19 | 1 | 19 | Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 3 |

| 011 | Nursery and Floriculture Production | Australian Capital Territory | 0-0 | 0 | 0 | Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 6 |

| 011 | Nursery and Floriculture Production | New South Wales | 200-30000 | 200 | 30000 | Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 0 |

| 011 | Nursery and Floriculture Production | New South Wales | 20-199 | 20 | 199 | Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 12 |

Along the way we’ll do some exploratory analysis. Here’s some summary data showing the top five states and ten industry divisions:

We can see that small businesses with less than 20 employees form the overwhelming number of business, and that perhaps half or more have no employees at all. Construction is the biggest industry (at the coarse one digit level of classification), followed by professional services and real estate. The pattern is similar across states, although Queensland and South Australia have relatively fewer professional and financial services firms than the other states. All of this is useful context.

I first chose 250,000 as the upper bound for the top bin (firms with 200 to 250,000 employees) because Wikipedia informs us that the largest firm in Australia by employee size is retailing giant Wesfarmers with 220,000. (Wesfarmers began as a farmer’s cooperative in my home state of Western Australia in 1914, but has grown and diversified - it now owns Bunnings, Kmart, Target and Officeworks among other things). But after some reflection I realised that Wesfarmers is almost certainly one of the 40,000 Australian Business Numbers “associated with complex structures” in this helpful diagram from the ABS on how the Business Counts is scoped. They would be a profiled unit for which the ABS maintains a record of its unit structure by direct contact with the business, and its various units likely are recorded as separate units in the data.

So, unable to use that 220,000 maximum employee size, I struggled to get a better figure for a maximum individual business unit, so decided on 30,000 more or less arbitrarily. It turns out this choice matters a lot if we are going to try to calculate average firm size directly from the counting binned data, but it doesn’t matter at all when fitting an explicit model the way I am here. Which is another argument in favour of doing it this way.

Here’s the entire data sourcing wrangling needed for this operation (asssuming frs is loaded with the ANZSIC lookup table):

Post continues after code excerpt

#------real data - business counts------------

download.file("https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&816502.xls&8165.0&Data%20Cubes&B164DBE8275CCE58CA2583A700121372&0&June%202014%20to%20June%202018&21.02.2019&Latest",

destfile = "bus_counts.xls", mode = "wb")

bus_counts_orig <- readxl::read_excel("bus_counts.xls" ,

sheet = "June 2018",

range = "A7:G4976",

col_types = c("text", "text", "text", rep("numeric", 4)))

names(bus_counts_orig) <- c("state", "code", "industry", "0-0", "1-19", "20-199", "200-30000")

bus_counts <- bus_counts_orig %>%

mutate(code = str_pad(code, 4, "left", "0")) %>%

filter(!grepl("^Total", industry) & code != "9999") %>%

filter((`0-0` + `1-19` + `20-199` + `200-30000`) > 0) %>%

gather(employees, freq, -state, -code, -industry) %>%

separate(employees, sep = "-", into = c("left", "right"), remove = FALSE) %>%

mutate(left = as.numeric(left),

right = as.numeric(right),

employees = fct_reorder(employees, -left)) %>%

left_join(dplyr::select(anzsic_4_abs, anzsic_class_code, anzsic_group_code, anzsic_group, division),

by = c("code" = "anzsic_class_code")) %>%

group_by(anzsic_group_code, anzsic_group, state, employees, left, right, division) %>%

summarise(freq = sum(freq)) %>%

arrange(anzsic_group_code) %>%

ungroup()

# how data will look:

kable(head(bus_counts)) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = "striped") %>%

write_clip()

# demo plot:

bus_counts %>%

mutate(division2 = fct_lump(division, 10, w = freq),

division2 = fct_reorder(division2, freq, .fun = sum),

state2 = fct_lump(state, 5, w = freq),

division2 = fct_relevel(division2, "Other", after = 0)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = division2, fill = employees, weight = freq)) +

geom_bar() +

facet_wrap(~state2) +

coord_flip() +

scale_y_continuous(label = comma, expand = c(0, 0)) +

labs(y = "Number of firms",

x = "",

fill = "Number of employees",

caption = "Source: ABS Count of Australian Businesses, analysis by freerangestats.info",

title = "Number of firms by industry division and number of employees") +

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.spacing = unit(5, "mm"),

panel.border = element_blank(),

axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Spectral", guide = guide_legend(reverse = TRUE))Modelling strategy and application

Whereas the simulated data in the first part of this post was estimates of time taken to perform a task, the underlying data here is a count of employees. So the Gamma distribution won’t be appropriate. The Poisson distribution is the usual starting point for modelling counts, but it doesn’t work in this case, so we relax it to a negative binomial distribution. One possible derivation of the negative binomial in this case would be to assume that the number of counts in any individual business has a Poisson distribution, but that even within state-industry combinations the mean of that distribution is itself a random variable. This feels pretty intuitive and plausible, and more importantly it seems to work.

To apply this with a minimum of code, I define a function to do the data reshaping needed for fitdistcens, estimate the parameters, and return the mean of the fitted distribution as a single number. This is suitable for use in dplyr’s summarise function after a group_by operation which means we can fit our models with only a few lines of code. I encountered uninteresting problems doing this with the whole dataset, so I decided to fit these models only to the manufacturing industries in three of the larger states. Even this was a computationally intensive task, so I make use of Hadley Wickham’s experimental multidplyr package which provides yet another way of performing parallel processing tasks in R. I think multidplyr looks promising because it integrates the familiar group_by approach from dplyr into partitioning of data into separate clusters for embarassingly parallel tasks (like fitting this distribution to many combinations of industry and state). This fits nicely into my workflow. The example usage I found on the net seemed to be from an old version of multidplyr (it looks like you used to be able to wrap your group_by command into partition but now they are sensibly separate) but it wasn’t hard to get things working.

Here’s the code for fitting all these models to every detailed manufacturing industry group in those three states. It takes less than a minute to run.

Post continues after code excerpt

bus_counts_small <- bus_counts %>%

filter(division == "Manufacturing" & state %in% c("New South Wales", "Victoria", "Queensland"))

#' @param d a data frame or tibble with columns including left, right and freq

#' @param keepdata passed through to fitdistcens

#' @param ... extra variables to pass to fitdistcens eg starting values for the estimation process

avg_finder <- function(d, keepdata = FALSE, ...){

d_bin <- as.data.frame(d[rep(1:nrow(d), d$freq), c("left", "right")])

fit <- fitdistrplus::fitdistcens(d_bin, "nbinom", keepdata = keepdata, ...)

return(fit$estimate[["mu"]])

}

# Meat manufacturing in NSW:

avg_finder(bus_counts_small[1:4, ])

# Meat manufacturing in Queensland:

avg_finder(bus_counts_small[5:8, ])

cluster <- new_cluster(7)

cluster_library(cluster, "fitdistrplus")

cluster_assign(cluster, avg_finder = avg_finder)

# calculate the simple ones using single processing dplyr for ease during dev:

bus_summary_simp <- bus_counts_small %>%

mutate(middle = (left + right) / 2,

just_above_left = (right - left) / 10 + left,

tiny_above_left = left * 1.1) %>%

group_by(anzsic_group, state) %>%

summarise(number_businesses = sum(freq),

crude_avg = sum(freq * middle) / sum(freq),

less_crude_avg = sum(freq * just_above_left) / sum(freq),

another_avg = sum(freq * tiny_above_left) / sum(freq))

# parallel processing for the negative binomial verions

bus_summary_nb <- bus_counts_small %>%

group_by(anzsic_group, state) %>%

partition(cluster = cluster) %>%

do(nb_avg = avg_finder(.)) %>%

collect() %>%

mutate(nb_avg = unlist(nb_avg))

bus_summary <- bus_summary_simp %>%

left_join(bus_summary_nb, by = c("anzsic_group", "state"))Results

So what do we see?

In the three plots below I compare three crude ways of estimating average firm size (in number of employees), on the horizontal axis, with the superior statistical modelling method taking into account the nature of binned data on the vertical axis. We can see that the choice of a crude way to assign an average employee number within each bin makes a huge difference. For the first two plots, I did this by taking either the mid point of each bin, or the point 10% of the way between the left and right bounds of the bin. Both of these methods give appallingly high overestimates of average firm size. But for the third plot, where I said the average number of employees in each bin was just 10% more than the lowest bound of the bin, we get bad under-estimates.

The shape of these plots depends not only on the method used for crude averaging within bins, but on the critical choice of the right-most bound of the highest bin (30,000 in my case). Differing choices for this value lead to more sensible estimates of average firm size, but this just shows how hopeless any naive method of using these bins is for assigning averages.

These are interesting results which illustrate how difficult it is estimate means of real world, highly skewed data - particularly so when the data has been clouded by binning for confidentialisation or convenience reasons. The mean has a breakdown point of zero, meaning that a single arbitrarily large value is enough to make the whole estimate meaningless (unlike eg the median, where 50% of the data needs to be problematic for this to happen). Having an unknown upper bound to a bin makes this problem almost certain when you are trying to recover a mean from the underlying data.

Here’s the code for those comparative plots.

Post continues after code excerpt

p1 <- bus_summary %>%

ggplot(aes(x = crude_avg, y = nb_avg, colour = anzsic_group)) +

facet_wrap(~state) +

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = 1) +

geom_point() +

theme(legend.position = "none") +

labs(x = "Average firm size calculated based on mid point of each bin\nDiagonal line shows where points would be if both methods agreed.",

y = "Average firm size calculated with negative binomial model",

title = "Mean number of employees in manufacturing firms estimated from binned data",

subtitle = "Inference based on mid point of bin delivers massive over-estimates")

p2 <- bus_summary %>%

ggplot(aes(x = less_crude_avg, y = nb_avg, colour = anzsic_group)) +

facet_wrap(~state) +

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = 1) +

geom_point() +

theme(legend.position = "none") +

labs(x = "Average firm size calculated based on 10% of way from left side of bin to right side\nDiagonal line shows where points would be if both methods agreed.",

y = "Average firm size calculated with negative binomial model",

title = "Mean number of employees in manufacturing firms estimated from binned data",

subtitle = "Using a point 10% of the distance from the left to the right still over-estimates very materially")

p3 <- bus_summary %>%

ggplot(aes(x = another_avg, y = nb_avg, colour = anzsic_group)) +

facet_wrap(~state) +

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = 1) +

geom_point() +

theme(legend.position = "none") +

labs(x = "Average firm size calculated based on left side of bin x 1.1\nDiagonal line shows where points would be if both methods agreed.",

y = "Average firm size calculated with negative binomial model",

title = "Mean number of employees in manufacturing firms estimated from binned data",

subtitle = "Using the (left-most point of the bin times 1.1) results in under-estimates")Conclusion

Don’t be naive in translating binned counts into estimates of the average of an underlying continuous distribution, whether that underlying distribution is a discrete count (like our real life example) or truly continuous (as in the simulated data). It’s much more accurate, and not much harder, to fit a statistical model of the underlying distribution and calculate the estimates of interest directly from that. This applies whether you are interested in the average, the sum, percentiles, variance or other more complex statistics.