If you’re serious about learning, you probably need to read a book at some point.

These days if you want to learn applied statistics and data science tools, you have amazing options in the form of blogs, Q&A sites, and massive open online courses and even videos on You Tube. Wikipedia is also an amazing reference resource on statistics.

I use all those things to learn new techniques and understand old ones better, but I also love reading books. No, I’m not one of those sentimental people who go on about the texture of paper; while I do like the look and feel of a “real” book and love having them around, it’s a pain the way the take up space, and the big majority of books I buy these days are on an e-reader. So when I say I like “books”, it’s something the depth and the focus that comes with a good book going deeply into a matter.

So here are my ten favourite applied statistics and data science books…

Necessarily this is a personal and idiosyncratic list. I haven’t read all the classics in the field and I certainly don’t have time to read all the new things that come out. But I read a fair number of books, including quite a few that I think are boring, or sub-standard, or unnecessary. This list below is of books that I come back to time and time again; and / or that made a huge impact on me when I read them at the right time.

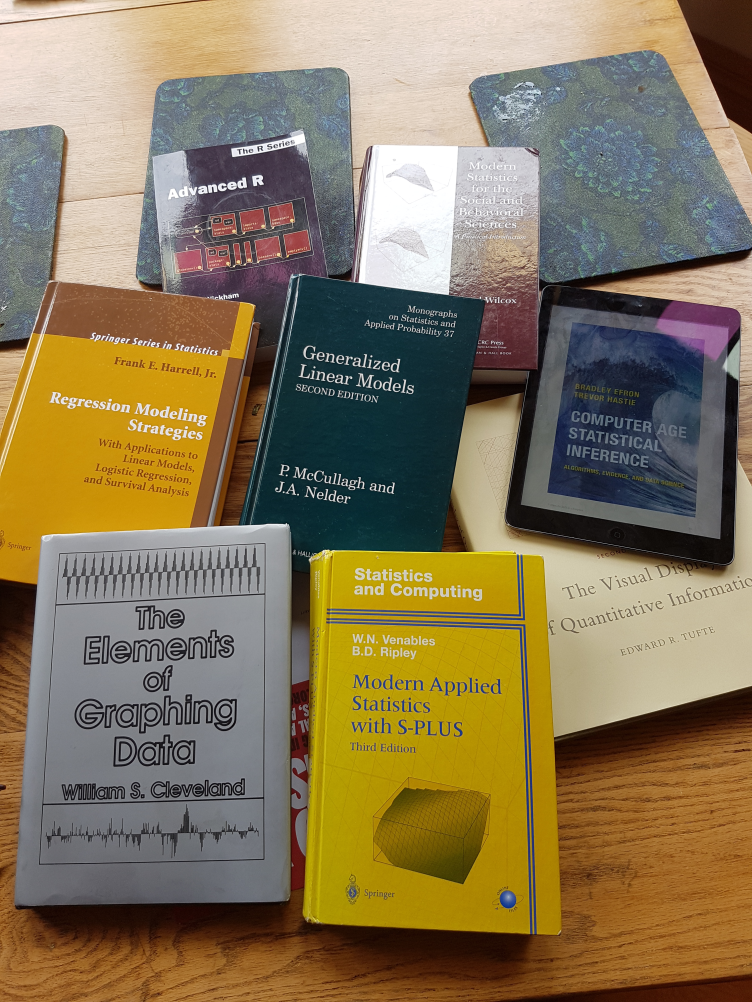

Only eight books in this photo because three of them I only have electronically, and I only had one tablet to put in the picture!

McCullagh and Nelder (1989), Generalized Linear Models.

What an amazing classic! A triumph of twentieth century statistics, which I think can really be seen as culminating in the Generalized Linear Model (GLM), bringing together things as diverse as the Chi Square test for independence in cross-tabs, Poisson, logistic and classical regression, and so much more. GLMs are everwhere, and they should probably be even more places than they are. As an un-named “good computer science expert” tweeted about by Robin Hanson said: “most firms that think they want advanced AI/ML really just need linear regression on cleaned-up data” (I agree, for what it’s worth). Or as Hadley Wickham pointed out on Quora, if he had to pick just one topic in statistics that every data scientist should know, it is linear models.

In this book we consider a class of statistical models that is a natural generalization of classical linear models. Generalized linear models include as special cases, linear regression and analysis-of-variance models, logit and probit models for quantal responses, log-linear models and multinomial response models for counts and some commonly used models for survival data. It is shown that the above models share a number of properties… These common properties enable us to study generalized linear models as a single class, rather than as an unrelated collection of special topics.

Harrell (2001, 2015), Regression Modeling Strategies.

If McCullagh and Nelder sets out the theory and application of GLMs, Harrell shows how to use them and subsequent developments in the real world in this amazing, principled yet pragmatic guide to the reality of regression modelling with tough, dirty data in realistic consulting-style applications. No-one who has understood this book will (I hope) make the mistake again of using step-wise variable selection and misinterpreting the p-values at the end. But the strength of the book is that it gives constructive guidance on steps for dealing with issues like missing data; variable and interaction specification in ways that won’t stuff up your inference; how far to go in relaxing linearity assumptions; validation; sample size relative to number of parameters for different types of models; model description and simplification; and different model-building approaches for predictive versus explanatory inference. Advice like:

It is only a mild oversimplification to say that a good overall strategy is to decide how many degrees of freedom can be ‘spent,’ where they should be spent, and then to spend them.

Efron and Hastie (2016), Computer-Age Statistical Inference: Algorithms, Evidence, and Data Science.

If GLMs were the crowning achievement of statistics in the twentieth century, a book like Efron and Hastie’s Computer-Age Statistical Inference is needed to put them in the context of the computationally-intensive revolution of the 1980s and beyond. Efron was the inventor of the bootstrap, which revolutionised statistics in the last decade of the twentieth century. Hastie is a big name in the “statistical learning” field, now more commonly called machine learning, and a pioneer with Tibshirani of the Generalized Additive Model which takes the GLM into the world of semi-parametric smoothing and beyond. This book is a fascinating combination of history, philosophy, theory and applications. An enormously valuable book, and should be read by anyone who wants to understand how and why modern statistics is different from how it has been conventionally taught.

The book is an examination of how statistics has evolved over the past sixty years - an aerial view of a vast subject, but seen from the height of a small plane, not a jetliner or satellite. The individual chapters take up a series of influential topics - generalized linear models, survival analysis, the jackknife and bootstrap, false-discovery rates, empirical Bayes, MCMC, neural nets, and a dozen more - describing for each the key methodological developments and their inferential justification.

There are no such subjects as Biological Inference or Astronomical Inference or Geological Inference. Why do we need “Statistical Inference”? The answer is simple: the natural sciences have nature to judge the accuracy of their ideas. Statistics operates one step back from Nature, most often interpreting the observations of natural scientists. Without Nature to serve as a disinterested referee, we need a system of mathematical logic for guidance and correction. Statistical inference is that system, distilled from two and a half centuries of data-analytic experience.

Tufte (1983, 1986, 1990), The Visual Display of Quantitative Information and its sequels

I’ll cheat here and pretend this ground-breaking book and its sequels Visual Explanations and Envisioning Information make up a single three-volume series - which is how they should be read. Beautifully designed and practicing what they preach, they set the standard for using visuals to understand and communicate patterns in data. Drawing on examples as diverse as train timetables and dancing instructions; introducing techniques like sparklines and small multiples; these books are just amazing and repay repeated study. I wish I lived up to their standards more.

Excellence in statistical graphics consists of complex ideas communicated with clarity, precision, and efficiency.

The world is complex, dynamic, multidmensional; the paper is static, flat. How are we to represent the rich visual world of experience and measurement on mere flatland?

Cleveland (1993, 1994) Visualizing Data and The Elements of Graphing Data

Don’t be fooled by the deliberately low-tech covers, these two books should be mandatory reading for anyone involved in visualising data - which means any practicing statistician or data scientist. Elements delves into the fundamentals of how human visual perception interacts with graphics; Visualizing Data goes into much more detail into specific graphing methods, taking Elements as its starting point. The famous Cleveland dot-plot - simple but powerful - comes from this research stream, as does the “trellis” framework of small multiples that led to lattice panels and ggplot2 facets in R, now a standard part of the toolkit for all series data workers. Cleveland was closely associated with S-Plus and has been hugely influential on the development of R, but these books are rightly tool-agnostic and approach the principles of the matter.

Visualization is critical to data analysis. It provides a front line of attack, revealing intricate structure in data that cannot be absorbed in any other way. We discover unimagined effects, and we challenge imagined ones.

Wilcox (2011), Modern Statistics for the Social and Behavioural Sciences: A Practical Introduction

This book came to me at the right time, when I was re-engaging with statistics after years of non-statistical work, and was simultaneously trying to remember how modelling and inference work and to learn R. While this book uses R in its examples, it is its clear explanatory and teaching style on statistical concepts that makes it so good. Its approach to robust statistics takes as a given that real world data is messy, with mixed distributions and outliers the norm. The bootstrap and simulations are used as fundamental to any inference and understanding; and introduced from the beginning, as they should be. This is a great book to learn statistics from, and a valuable corrective to earlier approaches that emphasised mathematics and unrealistic situations and datasets.

Included is a nontechnical description of three major insights regarding when routinely used methods perform well and when they are highly unsatisfactory…The second general goal is to describe and illustrate methods developed during the last half century that deal with known problems associated with classic techniques. There is increasing awareness among non-statisticians that these newer methods can make a considerable difference in the conclusions reached when analyzing data. Numerous illustrations are provided to support this view. An important point is that no single method is always best.

Venables and Ripley (1994, 1997, 2002, 2003), Modern Applied Statistics with S

Back in the 1990s when R was small and earlier editions of this book were focused on the S-Plus commercial implementation, it was one of the few texts around that dealt with the exploding range of new statistical and graphical methods available with the paradigm-changing S language. Now that open source R is all-dominant, the latest edition of this book is R-focused but it feels a little dated in today’s world of machine learning everywhere, 10,000 packages on CRAN, the tidyverse and ggplot. But I keep finding myself going back to it. No other book I know of deals with such a wide range of methods of care-free can-do spirit in combination with rigour. For me, this book epitomises a particular approach to statistics: lots of graphics, data exploration at the heart of everything, simulations to check things work the way one thinks, the bootstrap everywhere, and call in the best of breed methods for each challenge. From time series to survival analysis, neural nets (Ripley was a pioneer) to non-linear mixed effects models, this book is still a great overview of what’s possible.

Venables and Ripley both deserve the title of legend. I can’t imagine the equivalent of this book with its broad coverage being successfully written today (if someone knows of one, tell me in the comments!).

This book is about the modern developments in applied statistics which have been made possible by the widespread availability of workstations with high-resolution graphics and computational power equal to a mainframe of a few years ago.

Kuhn and Johnson (2013), Applied Predictive Modelling

This book is a successful blend of description of methods and their application. Eminently practical without being a software manual, it makes extensive use of Kuhn’s highly effective caret package for tuning and training predictive models, with cross-validation at the heart. This book is a great way to learn the fundamentals of predictive models such as random forests, neural networks, and the good old GLM and GAM.

We noticed that most machine learning books are focused either on the theoretical descriptions of models or are software manuals. Our book attempts to: give an intuitive description of models; illustrate the practical aspects of training them; and provide software and data sets so that readers can reproduce our work.

Wickham (2014), Advanced R

Accessible, up to date, and comprehensive, this book is an important read for anyone serious about using R for data analysis. Wickham is famous as the developer of ggplot2 (see below), the tidy data manifesto and the “tidyverse” that makes learning and using R easier and more powerful than ever before. But this book is not set in the tidyverse, it’s about how R works, and ultimately (my interpretation) how you can work with it rather than against it. It has excellent coverage of the fundamentals of R objects through to advice on making it work faster.

A scientific mindset is extremely helpful when learning R. If you don’t understand how something works, develop a hypothesis, design some experiments, run them, and record the resutls. This exercise is extremely useful since if you can’t figure something out and need to get help, you can easily show others what you tried. Also, when you learn the right answer, you’ll be mentally prepared to update your world view. When I clearly describe a problem to someone else (the art of creating a reproducible example), I often figure out the solution myself.

Wickham (2009), ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis

I bought this in 2011 as though it was a software manual, but instead it changed the way I think about graphics. Until a new edition is available, the existing code in this book is dated and the examples only a tiny slice of what ggplot2 now does so easily; but it is still a powerful read and potentially life changing. I wouldn’t use this book to learn R, or even ggplot (apart from the out-of-date code, I think the use of qplot was a mistake that makes it harder for beginners) - but if you can already use R, this is a powerful framework for unleashing the power of graphics. I now use the layered grammar of graphics - thinking in terms of layers of geoms and aesthetics, coordinate systems, scales and facets - as my approach to visualising data whether using ggplot2 or not. Wickham didn’t invent the grammar of graphics, but he made it possible for it be used at scale the way it is today.

The grammar is useful for you both as a user and as a potential developer of statistical graphics. As a user, it makes it easier for you to iteratively update a plot, changing a single feature at a time. The grammar is also useful because it suggests the high-level aspects of a plot that can be changed, giving you a framework to think about graphics, and hopefully shortening the distance from mind to paper. It also encourages the use of graphics customised to a particular problem, rather than relying on generic named graphics.

Edit 16 Jan 2017: Several readers pointed out the second edition is available, has up to date code and doesn’t use qplot - all of which just strengthens the case for this book.

Other books I also really like!

Ok, here’s some more books that I really like but didn’t make the cut of 10. Some of these I or my team at work use on an almost daily basis. Hyndman’s Forecasting Principles and Practice for example is the “pitched at just the right level” text we use to for training in applied time series analysis. Silge and Robinson’s tidytext will I think transform the analysis of textual data from an astonishingly messy hodge-podge (some of the worst R books I’ve read were pre-tidytext linguistic analysis ones) into a powerful, quick and simple framework. As a bonus, most of the books listed below are available in full text online for free. In no particular order:

- Edit 15 Jan 2017: Complex Surveys. Thomas Lumley’s definitive starting point for survey analysis in R, also a good clear explanation of how things like stratified sampling work even for non R users.

- Forecasting Principles and Practice. Succinct and clear exposition of the most standard and practical analytical methods for time series.

- Data Modeling Essentials. Statisticians should know more about how data is efficiently stored in databases.

- R for Data Science. Great introduction, coherent approach to analysis.

- The R Graphics Cookbook. Useful particularly for beginners.

- Practical Machine Learning with H2O. Great bilingual (Python/R) intro to the powerful H2O platform.

- R Packages. Practical guide to efficiency in building R packages from one of the best and most efficient in the game.

- Tidy Text Mining with R. Game changing introduction of system and good data sense to text data.

- Programming: Principles and Practice Using C++. Programming as done by people who see themselves as programmers first.

- S Programming. Before Wickham’s Advanced R, we had Venables’ S Programming. Great book for its time.

- The Signal and the Noise. Non-technical, compelling, on the challenges of forecasting.

- Aspects of Statistical Inference. A text from my uni days, I find this a powerful and philosophically consistent approach to thinking about inference under uncertainty.

- Econometric Models, Techniques and Applications. Another useful mid-level text. The techniques are dated by modern applied statistics standards, and much more dependent on both theory and linear models; but this is a great, clear exposition with enough maths to be precise, of standard late twentieth century econometrics.

There’s a few books I know of but haven’t read and feel I should: The Elements of Statistical Learning and Generalized Additive Models.

One influential book I don’t like

Overall, I don’t like Taleb’s The Black Swan. While some of what it has to say (the fallacy of seeing things as a controlled dice game) is very sound, it is riddled with straw man propaganda techniques when he gets on to his critique of statistics. I can only presume he received some exceptionally bad, old fashioned teaching of economics, econometrics and statistics, and didn’t take the trouble to look beyond to the amazing things that have been going on in this field. He writes as though no-one before him had noticed non-normal distributions or outliers. See my answer on Cross-Validated.

Some other people’s recommended books

Here are some others’ ideas:

- Berkeley Stats departments recommended books

- Quora Q&A including a Wiki of the best answers

- Questions about “best book” on Cross-Validated

- The market speaks - here are the best sellers on Amazon in this area

- Andrew Gelman’s top five books on statistics

- An interesting list of introductory statistics books on a user experience website