Seasonal air pollution in India

The motivation for this blog post was a conference paper I recently heard that analysed five years of daily pollution data in an India city with a non-seasonal auto-regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model. In discussion after the presentation, there were differing views on whether such data should be modelled with a seasonal approach, and I wanted to look at some data to see for myself (disclaimer - I was one of the pro-seasonal camp).

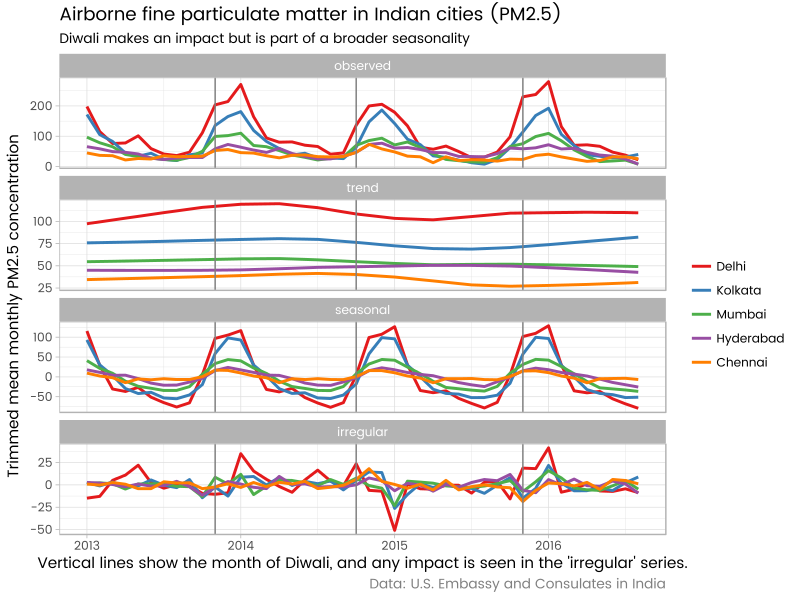

To cut to the chase, ultimately I was looking at this sort of obviously seasonal result:

Open Air Quality Data

But first thing was to get some data. I didn’t have access to the original data but was aware of other sources, with shorter time spans, but hopefully still enough for my purposes. My first call was the openaq Air Quality Data site and in particular the excellent ropenaq R package which speaks to the openaq API and makes it easy to access their data. This looked very promising, but the data available are for far too short a period for me. Here is the six months or so of data which is all that is available for Ahmedabad.

For the record, here’s the R code that downloaded that data (nearly 23,000 observations - many observations per day) and drew the graph, and also set up the session for everything else done in the rest of this post

# Might need to uncomment out and run these next two lines if not already installed:

# devtools::install_github("Ather-Energy/ggTimeSeries")

# devtools::install_github("masalmon/usaqmindia")

# load up functionality

library(ropenaq) # sourced from OpenAQ, see https://github.com/ropensci/ropenaq

library(ggplot2)

library(scales)

library(tidyverse)

library(usaqmindia) # sourced from US Air Quality Monitoring, see https://github.com/masalmon/usaqmindia

library(forecastHybrid)

library(seasonal) # for Diwali dates

library(ggseas)

library(ggmap)

library(lubridate)

library(RColorBrewer)

data(holiday) # will be using this for "diwali"

#============openaq experiment================

# based on the example on the package page on GitHub

how_many <- attr(aq_measurements(city = "Ahmedabad"), "meta")

n <- how_many$found # unfortunately only goes back to mid 2015

results_ls <- list()

# Limit is 1000 observations at once, so we bring them all in 1000 at a time:

for(i in 1:ceiling(n / 1000)){

results_ls[[i]] <- aq_measurements(country = "IN", city = "Ahmedabad",

date_from = "2010-01-01",

limit = 1000, page = i)

cat(i)

}

# convert into a data frame:

results_df <- do.call("rbind", results_ls) %>%

arrange(dateLocal)

# draw exploratory graph

results_df %>%

ggplot(aes(x = dateLocal, y = value)) +

facet_wrap(~parameter, ncol = 1, scales = "free_y") +

geom_line() +

ggtitle("Air pollutants in Ahmedabad, 2016") +

scale_y_continuous("Value", label = comma) +

labs(x = "", caption = "Source: OpenAQ")US Embassy and Consulate India Air Quality Monitoring

Luckily, the GitHub page for the ropenaq R package referenced a second R package, usaqmindia. This package has tidied and bundled up various source CSV and PDF files published by the US State Department on particulate matter concentrations in five Indian cities. The R package might not be completely current, but it looks pretty good. The particulate matter data are “commonly referred to as PM 2.5 because they are less than or equal to 2.5 microns in diameter”.

If your Indian geography is as rusty as mine you may appreciate this map of the five cities in question:

… which was made with this code using the ggmap R package (yes, I looked up those latitude and longitudes and copied and pasted them by hand - there are better ways of doing this in general, but for just five cities this was simplest):

#=========map of india========

cities <- data_frame(

city = c("Chennai", "Delhi", "Hyderabad", "Kolkata", "Mumbai"),

lat = c(13.067439, 28.644800, 17.387140, 22.572645, 19.0759837),

long = c(80.2784700, 77.216721, 78.491684 , 88.363892, 72.8776559)

)

india <- get_map("India", zoom = 5, maptype = "satellite")

ggmap(india) +

geom_text(data = cities, aes(x = long, y = lat, label = city), colour = "white") +

theme_nothing()The original data published by the US has multiple observations for the five cities for most days, and some days missing observations altogether. It’s not easy to spot patterns with this irregular data. Here’s how it looks out of the box:

… which was created with this:

#=========US Air Quality Monitoring===========

data("pm25_india")

pm25_india %>%

ggplot(aes(x = datetime, y = conc)) +

facet_wrap(~city, ncol = 1) +

geom_line()Those observations at concentration levels of 2000 looks suspicious for two reasons:

- they are so high compared to other levels. It’s plausible there are massive spikes some days, but it’s also plausible there’s something over-sensitive about the measuring device. I lack the subject matter expertise and resources to decide, so simply note that I might want to carefully use robust methods.

- they are exactly 2000, which looks like some kind of truncation (ie the real values may be more than 2000, and 2000 is just the maximum value of the censors).

To see patterns I want more regularised data. As a first go, I tried taking the trimmed mean average observation for each day. This gave me this graphic:

This is getting me somewhere. The patterns in Kolkata and Mumbai are looking plausibly regular now. This daily aggregation was made on the fly with this code:

# daily aggregation

pm25_india %>%

mutate(day = as.Date(datetime)) %>%

group_by(day, city) %>%

summarise(avvalue = mean(conc, tr = 0.1, na.rm = TRUE)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = day, y = avvalue)) +

facet_wrap(~city, ncol = 1, scales = "free_y") +

geom_line()Aggregate to monthly data

There are still a fair few days missing data altogether (apparent in the plot above by breaks in the lines). So I decided that for my purposes it made sense to aggregate the data by month. There’s all sorts of information that’s chucked out by this - variation on days within the month, and hours within the day; subtle treatment of the different number of days by month etc. But it’s good enough for my purposes of examining seasonality, and in fact this summarising/aggregation process is probably the best way to investigate a broad annual seasonal pattern. Just because we have large amount of irregular, granular data doesn’t mean we’re compelled to leave it in that state for analysis. Here’s how it looks when aggregated at a monthly level:

Looking at the pattern for each month, the seasonality is very apparent; there is much more particulate matter in the air in the winter-centred November to February period, most noticeably in the four northern cities (ie less so in Chennai). I don’t know enough about the subject matter to speculate if this is related purely to weather (the dominant factor being the May to November monsoon), or to human response to seasons.

We can decompose the monthly series into the trend, seasonal and random elements using the ggseas package to get a simultaneous view of scale and seasonality. The GitHub page of the usaqmindia R package draws attention to the importance of the Hindu Diwali ‘festival of lights’ - which involves fireworks, burning effigies, lamps, and general celebrations - for the particulate matter concentrations, so I’m interested in annotating graphics with those months. This gives us the graphic I started the post with:

Here’s the code that did the above aggregation and analysis.

# monthly aggregation graphic:

pm25_india %>%

mutate(mon = substring(datetime, 1, 7)) %>%

group_by(mon, city) %>%

summarise(avvalue = mean(conc, tr = 0.1, na.rm = TRUE)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(mon = as.Date(paste0(mon, "-15"))) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = mon, y = avvalue)) +

facet_wrap(~city, ncol = 1, scales = "free_y") +

geom_line(colour = "grey50", linetype = 2) +

stat_stl(s.window = 7, frequency = 12, colour = "steelblue", size = 1.2) +

ggtitle("Airborne fine particulate matter in Indian cities (PM2.5)",

subtitle = "Showing original and seasonally adjusted") +

labs(x = "Seasonal adjustment does not take Diwali into account",

y = "Trimmed mean monthly PM2.5 concentration",

caption = "Data: U.S. Embassy and Consulates in India")

# Create time series objects

pm25_monthly_df <- pm25_india %>%

mutate(mon = substring(datetime, 1, 7)) %>%

group_by(mon, city) %>%

summarise(avvalue = mean(conc, tr = 0.1, na.rm = TRUE)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

spread(city, avvalue)

pm25_monthly_ts <- pm25_monthly_df %>%

select(-mon) %>%

map(function(x){ts(x, start = c(2013, 1), frequency = 12)}) %>%

do.call(cbind, .)

# Month-plots

par(mfrow = c(2, 3), font.main = 1)

for(i in 1:5){

monthplot(pm25_monthly_ts[ , i], bty = "l",

ylab = "",

main = colnames(pm25_monthly_ts)[i])

grid()

}

#-------------Decomposition graphics----------------------

# named palette assigning a colour to each city

palette <- brewer.pal(5, "Set1")

names(palette) <- c("Delhi", "Kolkata", "Mumbai", "Hyderabad", "Chennai")

# Note that Diwali was in November 2013, October 2014, November 2015 in the relevant years

diwali[114:116]

# Decomposition graphic:

pm25_monthly_ts %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

mutate(time = time(pm25_monthly_ts),

month = time - floor(time)) %>%

gather(city, value, -time, -month) %>%

# imputation: if value is missing, give it mean for that month and city:

group_by(city, month) %>%

mutate(value = ifelse(is.na(value), mean(value, na.rm = TRUE), value)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

# order city levels for drawing legend (there are better ways for doing this programmatically):

mutate(city = factor(city, levels = c("Delhi", "Kolkata", "Mumbai", "Hyderabad", "Chennai"))) %>%

ggsdc(aes(x = time, y = value, colour = city), s.window = 7) +

geom_line(size = 1) +

theme(legend.position = "right")+

labs(colour = "", x = "Vertical lines show the month of Diwali, and any impact is seen in the 'irregular' series.",

y = "Trimmed mean monthly PM2.5 concentration",

caption = "Data: U.S. Embassy and Consulates in India") +

scale_colour_manual(values = palette) +

ggtitle("Airborne fine particulate matter in Indian cities (PM2.5)",

subtitle = "Diwali makes an impact but is part of a broader seasonality") +

geom_vline(xintercept = ((month(diwali) - 1) / 12 + year(diwali))[114:116], colour = "grey50")Delhi time series analysis

Diwali’s date is in a different month from year to year, which means we have a naturally occuring experiment that lets us distinguish between the underlying seasonal impact of any month, and the particular effect of Diwali. To investigate this further, I had a look at just the Delihi data, which is more complete than that of the other four cities even when aggregated to monthly level.

Here are graphics of the auto-correlation and partial auto-correlation functions of the Delhi monthly time series. These show the strength of relationship between any particular observation and lagged versions of the series. A lag of 1.0 means 12 months in this case. The patterns we see are typical of a series with a noticeable seasonal impact and a strong relationship to the observation of the previous month:

delhi <- pm25_monthly_ts[ , "Delhi"]

par(mfrow = c(1, 2), bty = "l", font.main = 1)

acf(delhi)

pacf(delhi)For analysis I was a little worried about second order stationarity, in particular whether the variance of monthly observations is higher when the mean observations are higher. I also had in mind the possibility of using a model for forecasting. While not shown in this already-too-long post, forecasting based on the original data hand a tendency for the lower range of the prediction interval to be negative, which isn’t possible and suggested the need for a transformation. All these problems can be fixed by a Box-Cox power transform. The BoxCox.lambda function used below uses Guerrero’s 1993 method for choosing a value of \(\lambda\) that minimises the coefficient of variation of the time series. With an estimated value of 0.21 for Delhi’s data (somewhere between a logarithm value of 0 and a square-root-like value of 0.5) this is well in the range of rule of thumb transformation commonly used for this sort of time series.

I use \(\lambda = 0.21\) for fitting an ARIMA model with a dummy variable for whether Diwali occurred in the month:

BoxCox.lambda(delhi) # about 0.21. Note that if we don't use this in forecasting there would be a tendency to forecast < 0

diwalix <- window(genhol(diwali), start = start(delhi), end = end(delhi))

mod0 <- auto.arima(delhi, xreg = diwalix, lambda = 0.21)

mod0That gives us these results, showing some modest evidence of a gentle drift downwards as well as a Diwali impact (0.46, with a standard error of 0.29 - well after all, it is only three years) within a seasonal ARIMA context

Series: delhi

ARIMA(1,0,0)(1,1,0)[12] with drift

Box Cox transformation: lambda= 0.21

Coefficients:

ar1 sar1 drift diwalix

0.5400 -0.7709 -0.0164 0.4626

s.e. 0.1561 0.0990 0.0082 0.2969

sigma^2 estimated as 0.1691: log likelihood=-20.41

AIC=50.83 AICc=53.14 BIC=58.16A 95% confidence interval confint(mod0) for the Diwali impact is between -0.12 and +1.04 on the transformed scale. This range includes zero so this analysis isn’t sufficient by itself to conclude it has an impact. However, the power of this test would be pretty low (one of the prices paid for by the aggregation to the monthly level) and my intuitive Bayesian inside would be happy to say it is more likely than not that there is some impact of Diwali on particulate matter in the atmosphere in Delhi.