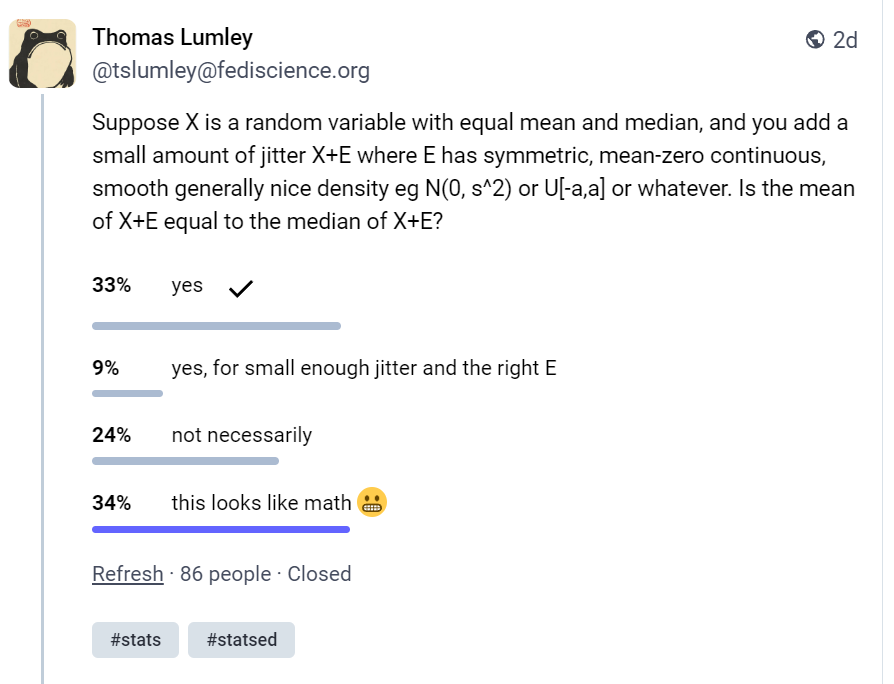

So I will fess up, I was one of the 34% of people who chose the first, incorrect answer on this quiz on Mastodon:

Original Toot, and explanatory responses, is available here.

My reasoning - and my only excuse is I didn’t think it through much - was simplistic. I imagined a distribution that had the same mean and median, and in my head all the two or three examples of such were symmetrical, like a normal or a uniform distribution. And I thought correctly that if you add some random noise to that, then the mean and median will stay the same.

But even when Thomas gave the correct answer (“not necessarily”) and explained that if there is a bit of local skew in the original distribution around the mean / median, I struggled to intuit why this is the case.

“Basically, to keep mean and median equal you need at least local symmetry around the mean. Otherwise the mean stays the same and the median moves”

Eventually I decided this way of thinking about it:

- First, adding random noise with mean zero leaves the mean of the original distribution unchanged - this is basic probability theory.

- When you add the noise, half the observations you are adding some value to were originally below the median and half are above it. On average the size of the noise is the same. But if your original distribution has some local skew, then observations on one side of the median will have a different chance of being perturbed by enough distance to “cross” the median (and hence change the median of the resulting distribution). So the median of the new distribution will be changed, in a direction that depends on the direction and level of the skew in the vicinity of the original mean/median.

To help me understand this I simulated some data. I built on Thomas’ suggestion in the Mastodon thread that (with a continuous distribution) “the examples tend to look a bit more contrived, but nothing essential changes. Take a positively skewed distribution, add a small bump far off to the left to move the mean down to equal the median. X+E will have median higher than mean.”

First, there’s the job of taking a skewed distribution and adding “a small bump on the left”. I chose to do this with a mixture distribution, 10 parts standard log-normal (ie e to the power of a N(0, 1) normal distribution) and 1 part normal with parameters chosen to make the mean and median identical. Now, there would be a way to analytically calculate the right parameters, but it’s much easier (for me) to find them numerically, so I made a function to generate the mixture given a set of parameters and used the optim() function for Nelder-Mead general-purpose numerical optimisation:

library(tidyverse)

# ------------------perturbing a skewed continues distribution

# Make a mixture distribution, 1 part normal and 10 parts standard exponential

# normal, and return the difference between the median and mean

mixture <- function(params, n = 1e6){

set.seed(123)

x1 <- exp(rnorm(n))

x2 <- rnorm(round(n /10), params[1], params[2])

x3 <- c(x1, x2)

y <- abs(median(x3)- mean(x3))

return(y)

}

# Find the set of parameters for the Normal part of a mixture

# that results in median and mean being as close as possible:

best <- optim(c(0.5, 1), mixture)

bestThis gives us:

> best

$par

[1] -6.421733 6.757088

$value

[1] 3.841277e-09

We can now generate our data from that - in this case 100,000 observations, to be safe - and we see that the results are in fact very close for mean and medain

# Generate data from that mixture

n <- 1e6

x <- c(rnorm(n/10, best$par[1], best$par[2]), exp(rnorm(n)))

# Mean and median are very close

c(mean(x), median(x))> c(mean(x), median(x))

[1] 0.9121877 0.9124763

All very good. Now I just want to add some random noise - say a standard N(0, 1) normal distribution - to each observation…

# perturb it a little

y <- x + rnorm(length(x))… and see what it does to the mean and median:

> # now the median has shifted but mean has stayed the same:

> c(mean(y), median(y))

[1] 0.9128076 1.0989388

> # compared to original:

> c(mean(x), median(x))

[1] 0.9121877 0.9124763

OK, as predicted. Can a visualisation help? Here’s one showing the original distribution and, superimposed, the version that has been perturbed with white noise. In this version, the horizontal axis has been given a modulus transform (one of the very first things I blogged about - a great way to visualise data that feels like it needs a logarithm or Cox-Box transform, but inconveniently includes negative values). This transform is good helping see the “bump” on the left, present in both the original and perturbed distribution:

However, the modulus transform makes it harder to understand the skew, so here’s the same chart with an untransformed x axis. This time we can see the original skew around the original mean and median, and perhaps this helps us understand what’s going on.

Seeing it like this, in the original scale, is useful for me at least, helping imagine adding random noise to the original distribution and seeing how doing that to the points just to the left of the original median pushes them over it (dragging the median up), whereas at least some of the points to the right of the median don’t get perturbed enough leftwards to push them over the median and drag it down.

Here’s the code for drawing those plots:

set.seed(124)

p3 <- tibble(`Original skewed variable` = x, `With extra jitter` = y) |>

sample_n(10000) |>

gather(variable, value) |>

ggplot(aes(x = value, colour = variable, fill = variable)) +

#geom_rug() +

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

scale_x_continuous(transform = scales::modulus_trans(p=0),

breaks = c(-40, -20, -10, -5, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 40)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(x), colour = "red") +

geom_vline(xintercept = median(y), colour = "steelblue") +

annotate("text", x = 1.3, y = 0.6, label = "Post-jitter median", hjust = 0,

colour = "steelblue") +

annotate("text", x = 0.86, y = 0.6,

label = "Original equal mean and median, also post-jitter mean",

hjust = 1, colour = "red") +

labs(x = "Value (modulus transformed scale)", y = "Density", colour = "", fill = "",

title = "Adding jitter to a mixture of a skewed and symmetrical distributions",

subtitle = "The mean stays the same with the jitter, but the median moves if the distribution wasn't symmetrical around the original mean.",

caption = "Based on an idea in a toot by Thomas Lumley")

# with transform:

print(p3)

# without transform:

p4 <- p3 +

scale_x_continuous(limits = c(-10, 10)) +

labs(x = "Value (untransformed, axis truncated)")

print(p4)That’s all folks. What out for those tricky distributions. Actually, although the simulated example above with exactly matching mean and median is obviously contrived, a distibution that is a mix of a skewed log-normal with a lump of something far to the left isn’t unusual in some economic areas - like firms’ profits or individuals’ incomes (mostly they are shaped log normal and strictly positive, but a small selection make some degree of a loss, and it’s definitely a mixture of two distributions not some easily-described single mathematical function).